Guide / NHS audit committee handbook

This handbook is designed to help NHS governing bodies and audit committees in reviewing and reassessing their system of governance, risk management, and control. This is to make sure the governance remains effective and fit for purpose, whilst also ensuring that there is a robust system of assurance to evidence it.

While every care has been taken in the preparation of this briefing, the HFMA cannot in any circumstances accept responsibility for errors or omissions and are not responsible for any loss occasioned to any person or organisation acting of refraining from action as a result of any material within it.

The NHS is always changing and developing – this edition reflects the structures and processes in place as at writing. We are keen to obtain any feedback. Please forward your comments to [email protected] or the address above.

Free printed copies for NHS organisations

We are offering 5 free printed copies of this guide to NHS organisations. Find out more and register for free copies.

Foreword

The HFMA NHS audit committee handbook (the handbook), developed by the HFMA Governance and Audit Committee, is designed to help NHS governing bodies and audit committees as they review and continually re-assess their system of governance, risk management and control to ensure that it remains effective and ‘fit for purpose’, while also ensuring that there is a robust system of assurance to evidence it.

The handbook has had a complete rewrite and replaces previous editions, including the last full hard copy version printed in 2018 and the online supplement published in 2022. The HFMA is grateful for the support provided by NHS England in providing this handbook. The handbook is freely available online and will be updated on a regular basis to ensure it remains relevant.

In terms of its content, the handbook starts by explaining why governing bodies need audit committees and how they provide support in fulfilling statutory duties and organisational objectives. It then looks at how audit committees should be set up, before moving on to focus in detail on what they do and how they work with others. Practical examples are included throughout to bring the theory to life and cross references to further sources of guidance are included. The appendices also include example tools such as self-assessment checklists, agendas and terms of reference, as well as a comprehensive glossary of terms.

Further detail on how the NHS finance regime works, as well as the wider landscape in which it operates can be found in the on-line HFMA introductory guide to NHS finance

The handbook applies to NHS organisations in England. However, the principles and much of the practical guidance is broadly relevant across the rest of the United Kingdom.

Audit committees and their members continue to play a crucial role in the governance of every NHS organisation and members must take seriously their responsibility for scrutinising the risks and controls affecting every aspect of the business – not just in the finance and financial management sphere. We hope that you find this handbook of real practical benefit as you carry out this demanding role.

The handbook is developed under the direction of the HFMA's Governance and Audit Committee

Nicky Lloyd,

Chair, HFMA Governance and Audit Committee

Chief finance officer, The Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust

Contents

Foreword

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 2: Constitutional position

Chapter 3: Membership and attendance

Chapter 4: Formality of meetings

Chapter 5: Private meetings and rights of access

Chapter 6: Committee effectiveness

Chapter 7: Committee reporting

Chapter 8: Annual report and accounts

Chapter 9: Internal audit

Chapter 10: External audit

Chapter 11: Counter fraud

Chapter 12: Other assurance functions

Chapter 13: Governance

Chapter 14: Risk management

Chapter 15: Assurance

Chapter 16: Speaking up and whistleblowing

Chapter 17: Information governance and cyber security

Chapter 18: Exception reporting

Chapter 19: Audit committees and integrated care systems

Chapter 20: Current issues

Appendix A: Example terms of reference

Appendix B: Self-assessment checklists

Appendix C: Example agenda and timetable

Appendix D: Glossary

Chapter 1: Introduction

Overview

An NHS audit committee brings an independent and objective oversight of an organisation’s arrangements for governance, risk management and internal control, protecting the interests of stakeholders. This chapter looks at how its role has evolved from an initial focus on financial reporting to, on behalf of the board, a corporate-wide remit. The role that it plays in terms of risk assurance will depend on how the organisation has agreed its arrangements.

1.1 Purpose

Audit committees were first introduced in the private sector in the late 1930s by the New York Stock Exchange and gained more traction in the 1970s and 1980s following corporate governance and financial reporting failings. At their heart is the role of the independent non-executive directors to protect the interest of shareholders with regards to the truth and fairness of financial reporting and, subsequently, on the operation of the organisation that creates shareholder value.

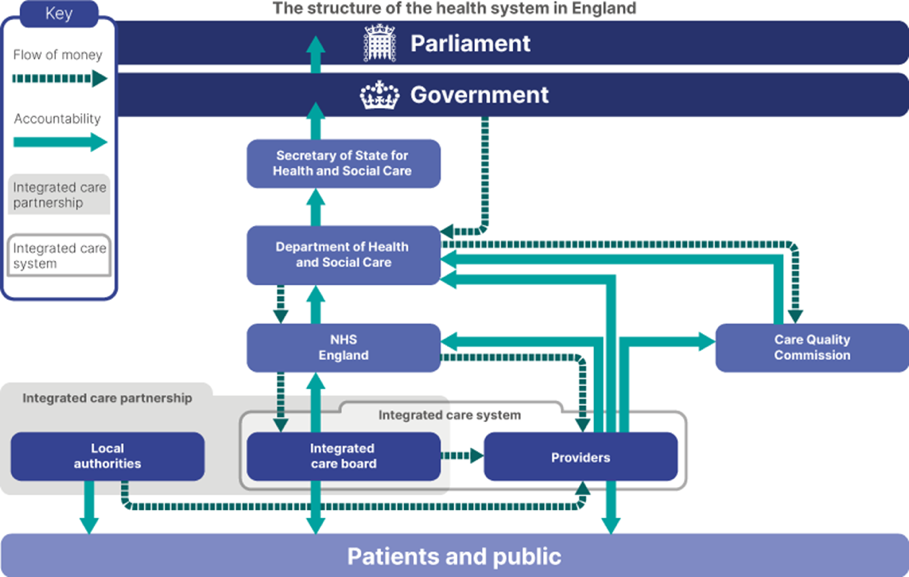

Within the UK public sector, and the NHS in particular, the independent non-executive directors carry out the same function, but to protect the interests of a much wider range of stakeholders (from the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) to patients). While the initial focus of audit committees was on financial reporting (and financial control) the remit has broadened to cover both financial and non-financial areas, best described as the system of governance, risk management and internal control, across the whole of the organisation’s activities (clinical and non-clinical), that supports the achievement of the organisation’s objectives.

As with many corporate governance developments over the years, failings in corporate governance continue to impact on the role and responsibilities of audit committees.

1.2 Overview of current role

The remit of the committee is set out in the detailed terms of reference (see models in appendix A), but the main aspects that it covers are:

- establishing and maintaining an effective system of governance, risk management and internal control, across the whole of the organisation’s activities

- ensuring that there is an effective internal audit function

- reviewing the work and findings of the external auditors

- receiving updates from the local counter fraud service on national and local matters

- reviewing the findings of other significant assurance functions

- satisfying itself that the organisation has adequate arrangements in place for counter fraud, bribery and corruption

- monitoring the integrity of the financial statements

- reviewing the effectiveness of the arrangements in place for allowing staff (and contractors) to raise (in confidence) concerns about possible improprieties.

Most of the above aspects are inter-related, but the ultimate goal is to ensure that the organisation is being managed effectively and thereby meeting its strategic objectives, including safeguarding taxpayer resources so that they are utilised for the benefit of delivering patient services.

1.3 History in the NHS

Audit committees became regular parts of the governance of NHS bodies in the 1980s, particularly with the creation of the purchaser/provider split and the greater autonomy given to NHS trusts (and subsequently NHS foundation trusts).

A series of corporate governance failings in the 1990s led to a number of initiatives to improve governance; from model standing orders (SOs), standing financial instructions (SFIs) and schemes of delegations (SoDs) to greater guidance for audit committees. Continuing corporate governance failings led to further developments, most notably in areas of clinical governance, but at the same time widening the focus of audit committees from systems of internal ‘financial’ control to systems of internal control, encompassing the whole organisation.

Developments have continued apace, most notably as a result of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry

1.4 What type of committee?

As audit committees have developed, both in the NHS and the wider public sector, three broad models have evolved:

- the ‘audit’ committee: this type of committee focuses on audit (internal and external) and uses the work of the auditors to assist in its oversight (such as internal audit review of the system of risk management)

- the ‘audit and risk’ committee: this type of committee takes a more active oversight of the system of risk management, and associated assurance framework, ensuring that the system works as a whole (such as ensuring that other committees provide oversight of risks)

- the ‘audit and risk assurance’ committee: this type of committee takes a more active role in looking at the management of individual risks, the effectiveness of controls and the sources of assurance.

The way that an organisation’s audit committee works, in terms of which model above is adopted, should depend on how it has arranged its governance around risk management and assurance.

1.5 Role of the audit committee member

The audit committee is unique, in a number of ways, to other committees and groups within an NHS organisation, not just because its membership is made up of non-executives (similar to a nomination and remuneration committee), but because its members need to look at issues from a different perspective; being independent and objective. This can mean that the members may need to say things that are unpopular or that executive management may not wish to hear (speaking truth to power) to ensure that the right thing is done.

It is important that, while committee members may deal with issues in detail, they also need to be able to take a ‘step back’, using the advantage of non-executives not being swamped by daily operational pressures. They also need to bring – proportionately – their depth of knowledge and experience from their careers, many of which may not have been within the NHS, so that they can compare and contrast and use that independent perspective.

As set out by the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW)

Audit committee members, as for all board members, need to ensure that they are competent to undertake their role. The audit committee member role does not necessarily require expertise (other than that one member should be financially competent), but they should ensure that they understand their role.

Executive and other attendees need to understand the importance of this constructive challenge and the benefit that it can bring.

1.6 Being ‘independent’

Central to the effectiveness of the audit committee is that its members are independent of day-to-day management and therefore not conflicted in their work, so that that they can bring their professional judgement to issues under consideration. This is why membership is limited to non-executive directors and excludes the chair.

1.7 Being ‘objective’

Associated with independence is the fact that members of the audit committee should bring objective judgement to their work, basing their conclusions on the facts and evidence presented to them, avoiding any bias or undue weighting of opinions.

A key skill of audit committee members is therefore to listen to the evidence provided (or more realistically to read the papers), hence the name of the audit committee derived from the Latin ‘audio’ meaning to listen or hear.

The judgement that they bring should be in the best interest of the stakeholders of the organisation as a whole – primarily that of the patients and taxpayers.

It is important that one member, who is usually the chair of the audit committee, but need not necessarily be so, has professional financial training and is a member of a recognised professional body, which requires up to date continuous professional development (CPD) to provide the appropriate level of professional leadership for this important role.

1.8 Assurance versus re-assurance

Assurance is gained through information, evidence and triangulation that validates an assertion, whereas re-assurance comes from an individual providing comfort to allay a concern, without evidence to support the assertion. The role of the committee is to challenge assurances, and not (overly) rely on re-assurances.

1.9 Effectiveness and compliance

An audit committee’s key role is to look at the ‘effectiveness’ of internal control systems (more than economy and efficiency, using the traditional ‘three E’s’ of value for money (VFM)). In this context, effectiveness is seen in the light of achievement of objectives, the management of the risks to those objectives and the operation of the controls and mitigations put in place for those risks.

Once management have designed their systems of control, including the desired mitigations and controls that are required, then being assured on the level of compliance with the policies and procedures, and how effective they are at achieving the stated objectives, becomes a key role for the committee.

Key learning points

- Audit committees started with a focus on resolving disputes on financial reporting and stewardship between management and external auditors.

Over time their remit has grown to where they now oversee the organisation’s arrangements for governance, risk management and internal control.

Some of this they directly oversee, for other areas they need to satisfy themselves that they are being appropriately covered elsewhere.

Audit committee members (all of whom are non-executive) must be independent and objective in undertaking their role.

Chapter 2: Constitutional position

Overview

All NHS organisations must have an audit committee and they should carry out their role as delegated by the board under terms of reference.

2.1 Statutory basis

Every NHS organisation is required to have an audit committee that reports to its board. The formal requirements to have an audit committee are set out in different documents, depending on the organisation.

For integrated care boards (ICBs), guidance on ICB constitutions states:

The audit committee is accountable to the board and provides an independent and objective view of the ICB’s compliance with its statutory responsibilities. The committee is responsible for arranging appropriate internal and external audits. It will be chaired by a non-executive board member who has qualifications, expertise or experience that enables them to express credible opinions on finance and audit matters.'

For NHS trusts and NHS foundation trusts, paragraph 2.1 of the Code of Governance for NHS provider trusts

NHS governing bodies have an oversight role, as part of this they are responsible for putting in place governance structures and processes to:

ensure the organisation operates effectively and meets its statutory and strategic objectives

provide it (the board) with assurance that this is the case

Audit committees play a key role in supporting the board by critically reviewing and reporting on the relevance and robustness of the governance structures and assurance processes (on risk management and systems of control) on which the board places reliance.

2.2 Links to other committees

In its role of assessing the overall effectiveness of governance arrangements, the audit committee will need to work with other board committees to avoid both duplication and omission, as well as to understand where the various assurance flows come from and go to. At a high level it should assure itself that, for instance, clinical governance is being effectively overseen by a quality committee.

This does not mean that it needs to have detailed oversight of the work of the committee, but that such work is within the committee’s remit.

2.3 Terms of reference

The board should adopt formal terms of reference that clarify the authority and responsibilities of the audit committee, that are also consistent with the body’s wider constitution.

Example terms of reference are provided in Appendix A, with separate examples for NHS provider organisations and ICBs. These seek to represent best practices, but individual organisations may wish to tailor them to fit their own governance arrangements. In line with good corporate governance practices, there is a general presumption of ‘comply or explain’ and if model terms of reference are not adopted, the material differences should be explained.

2.4 Authority

The audit committee has no executive responsibilities and must not take on any roles or duties that are not relevant to those of an audit committee.

The committee’s terms of reference provide specific authority to investigate matters within its remit, require information and co-operation from employees and can access legal or professional advice. This tends to happen by exception, and usually when there has been a breakdown in controls, crystallisation of a risk, failure of a project or a near miss.

Where decisions are needed, it would be expected that the audit committee would report to the governing body (see chapter 7) and advise on the decisions to be made.

Key learning points

- All NHS organisations are required to have an audit committee.

- They work to terms of reference delegated by the board and work with other committees.

- The audit committee has no executive powers, unless expressly delegated, but has influence.

Chapter 3: Membership and attendance

Overview

Members of the audit committee are drawn from the non-executive members of the organisation, as appointed by the organisation’s governing body, to maintain its independence and objectivity. It is usual for the chief finance officer (CFO), external auditors and internal auditors to attend all meetings, along with secretariat support.

3.1 Membership

Membership of the audit committee is limited to non-executive directors of the governing body, to reinforce its role as an independent and objective oversight body, but it excludes the chair of the governing body. Members should not be employed by the organisation other than in their capacity as non-executive directors.

Members are appointed by the governing body, including the committee chair. The chair is a critical appointment for the organisation. HM Treasury guidance requires the audit committee chair to be a non-executive board member with relevant experience

To maintain independence the chair of the audit committee should not chair any other committees. Ideally, they should not be a member of any other committee, although in some cases this may be impractical due to the number of non-executive directors available to cover all required committees.

One of the members of the audit committee (and it need not be the committee chair, although often is) should have recent and relevant financial experience, so as to allow the committee a degree of expertise in this area; such as in financial reporting or working with auditors. There may be value in having some members of the audit committee who are also members of other sub-committees; primarily around quality, safety, finance and performance. This allows a more rounded view of how assurances are covered across committees.

It is not usual for the senior independent director (SID)

Some audit committees have included lay members in their membership (in other words, they are not non-executive directors (NEDs), but provide independence and expertise). These members would not be voting members (if a vote were needed), but would take a full part in proceedings.

As set out in the model terms of reference for integrated care boards (ICBs) (see appendix A), 'when determining the membership of the committee, active consideration will be made to diversity and equality.'

Membership of the audit committee should be disclosed in the organisation’s directors’/members’ report within the annual report.

3.2 Attendance

Attendance at an audit committee meeting is at the invitation of the committee chair.

However, it would be expected that the following would attend for most, or all, parts of each meeting:

the chief finance officer

the head of internal audit (or representative of the internal audit service)

a representative from external audit

the board secretary or equivalent.

While the above would be expected to attend to address the agenda items that relate to their work, the committee will benefit from contributions from them to other agenda items, given the experience and knowledge that they bring.

In addition, the following would be expected to attend more regularly, but might not be expected to attend all meetings, or all parts of a meeting:

the local counter fraud specialist (LCFS) (or representative of the service) – usually a minimum of twice a year

the governance lead, such as the company secretary

the risk management lead.

On occasions the following might be asked to attend:

representative from NHS Counter Fraud Authority

representative from wider assurance providers

executive directors and senior managers where appropriate.

It would be expected that, at the invitation of the committee chair, the chair and chief executive officer (CEO) would attend some (or part of some) meetings and it is good practice for them to provide the audit committee with a business update including pertinent issues that may be of particular interest to the committee. However, this should be managed to maintain independence, being clear that they do not have a right of attendance.

The chair would attend to ensure that the committee is operating as expected and that the non-executives are carrying out their tasks appropriately.

The CEO, as an accountable officer, would be particularly expected to attend for items around the annual report and accounts, including the annual governance statement, for which they are directly accountable.

3.3 Role of the audit committee chair

The role of the chair of the audit committee is, in many respects, the same as that of any committee chair (liaising with secretariat over agendas, agreeing draft minutes, chairing the meeting, and so on).

For NHS audit committees there are some particular aspects to consider:

- building relationships with internal audit, external audit and LCFS (as well as the security management specialist where they do not report elsewhere) between meetings so that they are clear that their right of access to the audit committee (via the chair) is wholly supported - this should include scheduled conversations between meetings or ahead of specific events

- working with other committee chairs to ensure that the oversight of the individual and collective committees is most effective; avoiding duplication and omission - this is particularly so in areas around risk assurance.

The audit chair also has a key role in supporting the CFO and developing a strong working relationship, particularly as the role of the CFO has become much more complicated in recent years.

3.4 Conflicts of interest

NHS England defines conflicts of interest are defined as:

'A set of circumstances by which a reasonable person would consider that an individual’s ability to apply judgement or act, in the context of delivering, commissioning or assuring taxpayer-funded health and care services is, or could be, impaired or influenced by another interest they hold.'

NHS England, Managing conflicts of interest: guidance for staff and organisations, August 2017

As with any meeting, any conflicts of interests – perceived or actual – should be formally declared and appropriately managed. Examples include: recent employment with the health service body; close family ties to its directors, members, advisors or senior employees; or a material business relationship with the health service body. For NHS audit committees, more particular conflicts could include relationships with audit providers (internal and external), particularly around the time of procurement for the services.

The Health Care Act of 2022

3.5 Competence and training

Members of the audit committee should ensure that, individually, they are competent in their understanding of audit and risk assurance; including corporate governance, risk management, internal control and assurance.

In addition to having one member with particular competency in financial reporting and audit, the audit committee members should look – individually or collectively – to have more advanced competency in such areas as procurement and compliance.

The committee should regularly consider its own training needs so that members have the skills that will allow them to perform their role effectively. As well as a basic understanding of finance and internal control, along with their role as audit committee members, this should include a good understanding of the local finance and governance arrangements across health and care, and wider partners, in the local system (see further consideration of system working in chapter 19).

The board secretary or governance lead should seek to support the members (and attenders) in accessing suitable training and development.

3.6 Behaviour

Members’ behaviour needs to embody the highest ethical standards, both as generally accepted in public life (see Nolan principles

NHS England’s Fit and proper person test framework for board members

good character

possessing the qualifications, competence, skills required and experience

financial soundness.

As well as meeting these requirements, they should ensure that they provide an example by being pro-active in their compliance.

The Nolan principles of public lifeCommittee on Standards in Public Life, The seven principles of public life, May 1995

Key learning points

Membership of the audit committee is limited to non-executive members of the board.

The CFO, along with representatives from external audit, internal audit and the local counter-fraud specialist would normally be expected to attend audit committee meetings.

The role of the committee chair is important in not only running an effective meeting but also building relationships with auditors and management.

All members and attendees should ensure that they maintain their competence and are supported in their training and development.

Chapter 4: Formality of meetings

Overview

Formal meetings of the committee should cover the requirements within the terms of reference, generally following an annual cycle with some regular items at each meeting. Good secretariat support will help the effectiveness of meetings, both in their arrangement, commissioning of papers and recording of minutes.

4.1 Frequency of meetings

It is normal for audit committees to meet four or five times a year, with a possible additional meeting to specifically review the annual report and accounts.

These meetings should fit into both the audit cycle (planning, progress and reporting) for internal and external audit, as well as the financial year (annual report and accounts planning and reporting). Some elements of the audit committee remit are subject to a periodic review (often annually), such as its own self effectiveness review, or reviewing arrangements for raising concerns. These can best be scheduled at those meetings that are likely to have fewer substantial agenda items.

4.2 Quoracy

Membership of the committee is limited to the non-executive directors (see chapter 3), with an expected minimum of three. Quoracy is therefore normally set at two, although a larger membership might have a different quoracy.

If quoracy cannot be achieved there can be options to invite other non-executive directors to attend for a single meeting (excluding the chair), or the meeting can go ahead and any actions or decisions (dependent on the nature) could be ratified at the next committee meeting, or by the next board. Neither of these is ideal, but pragmatic if the reason for the lack of quoracy is short-term and the papers have already been read and the attenders are available.

4.3 Agenda and timetable

The chair, with secretariat support, should ensure that the remit of the committee, as set out in its terms of reference, is covered over the course of the year in its workplan, with some items occurring at each committee meeting and others less regularly.

Example items to be covered in agendas over an audit year is set out in appendix C.

In commissioning papers for the committee meetings, particularly from managers who do not regularly attend committee meetings, it is important that the purpose of the agenda item is explained, as well as the expectations from the audit committee members. It would be appropriate for the board secretary, or CFO/executive lead to offer this support to managers, while in some circumstances a pre-meet with the audit committee chair might be of value.

4.4 Delegated decision-making

While the audit committee is a non-executive committee, and does not normally have any decision-making powers, some decisions can be delegated to the committee by the governing body. These tend to be around the detailed review of the annual report and accounts, but can also include investigation into specific incidents or deep dives into particular topics.

The committee will also be involved in the decisions about the appointment of internal auditors (see chapter 9), external auditors (see chapter 10) and local counter fraud specialists (see chapter 11).

4.5 Secretariat support

Secretariat support, which is more than just the logistics of arranging the meeting and co-ordinating the papers – important as they are – is critical in ensuring that the audit committee is effective and keeps to its remit.

The audit committee secretary is commonly the organisation’s secretary or governance lead. The secretary should meet with the chair of the committee, between meetings, to help plan the next agenda and the commissioning of papers.

Draft minutes of each meeting should initially be shared with the chair and executive lead, as soon as practical after the meeting, to confirm accuracy and ensure that all actions have been identified.

The secretary should take an active lead in following up the actions from each meeting, usually maintained in a log, and reminding action owners of when the action is due.

4.6 Quality of papers

It is best practice for any committee to give guidance on what it requires from the papers that support the agenda. It is important that, when commissioning papers, the secretariat are clear that the paper is designed to inform a discussion and therefore give a steer on what that discussion needs to cover, what information is needed (and not needed) and what outcome the agenda item is seeking to achieve (assurance on an area, an action that will need to be implemented, and so on).

In some instances, such as for external audit, the content of their reports is set out in professional standards. Other functions, such as internal audit and counter fraud, will also have standard practices.

Some organisations have a standard practice of header sheets that help summarise the main points. The point of this is to help the committee by highlighting the critical issues that need drawing to the committee’s attention, for discussion or for action.

4.7 Quality of minutes

Different organisations will have different policies on how minutes are produced, including the level of detail that is recorded. It is important, particularly with regards to sensitive discussions, that the minutes reflect what has been discussed, how well the discussion went, the different opinions heard and the level of importance given to the agenda item.

Actions that come out of this discussion need to be clearly recorded and kept on an action log that the secretariat keep up to date.

4.8 Collaboration with other audit committees

There is the ability, in some circumstances, for audit committees to work together through collaborative audit committee arrangements. This is a developing area with increasing examples of committees in common resulting from group models between NHS organisations.

A committee in common is defined by NHS Providers as ‘an arrangement where each participating organisation uses its statutory powers to establish a statutory committee which has delegated functions or decision-making powers in respect of the parent organisation only. Decisions delegated to the committees do not need to be referred back to the boards of the participating organisations. Decisions are made by the committees collectively and all committees need to be in agreement for decisions to be binding. Terms of reference for each committee will be shared or aligned’

As integrated care systems (ICSs) mature and look at different ways of working there needs to be clarity on the relative roles and responsibilities. Chapters 19 and 20 look at some of these broader issues.

Key learning points

The audit committee should meet for a minimum of four times a year (possibly holding one extra meeting for the annual report and accounts).

The agenda for each meeting can be supported by an annual workplan that ensures that the terms of reference are met.

Good secretariat support will ensure that, in meeting the terms of reference, papers that are commissioned are clear in what is being sought from them, and that minutes accurately reflect the discussion and actions to be taken forward.

Chapter 5: Private meetings and rights of access

Overview

Audit committee members should have time to meet on their own, as well as time to meet with auditors without management present. Auditors should also have the right of access to the chair of the committee, when they wish to raise issues that are sensitive or have been unable to resolve with management.

5.1 Private meetings: committee members only

It is sometimes useful for just the committee members to meet on their own, without anyone else in attendance. This is an opportunity for them to discuss the agenda, the matters being discussed and any particular issues that they want to raise or discuss. Given that most non-executives have busy lives, there may not have been a chance for this to have happened before.

It would be usual, after such a meeting, to then note this meeting with the attendees in the formal meeting and any points that they may wish to highlight. This is in part to re-assure those attending the full committee meeting about what has been covered, as well as to keep a record and maintain a culture of openness.

There may be instances where the committee meets with just secretariat support, especially if they are undertaking a specific review into a piece of work or investigating a break down in controls. In such instances this meeting should be appropriately minuted and regarded as a formal meeting.

A final alternative would be where the committee meets with just a few attendees. This would primarily be where there was a potential conflict of interest, and usually that would be to discuss the tendering and appointment of internal or external audit. Again, this meeting would be a formal meeting, duly minuted but the contents kept confidential.

5.2 Private meetings with auditors

The more normal practice is for the committee to meet with representatives of internal and external audit, as well as the local counter fraud specialist, outside of the formal meeting (normally before). This can be either meeting with them individually, or as a group, or some permutation of the two.

The point of this meeting is to allow the auditors to raise issues that they might feel hindered in raising with management in attendance, but it can also be used by committee members to seek clarification on details in the papers that they may feel more comfortable asking outside of the meeting. It is also an opportunity for committee members to ask about working relationships, both with management but also between the auditors and with the local counter fraud specialist.

In some respects, given the right of access, nothing should emerge from these meetings that comes as a surprise.

It is for the committee chair to agree how any matters that do arise in these discussions are handled. They need to be aware that, to benefit from these sessions, confidentiality needs to be maintained where necessary, and that auditors are reassured on this point. Poor handling of this could have an adverse impact on the relationships between management and auditors.

The sort of questions and topics that could be covered are set out below.

Example questions that could be covered in private meetings with auditors:

5.3 Right of access

Both sets of auditors, and the local counter fraud specialist, have a right of access to the audit committee, which is primarily carried out through the committee chair. This is a vitally important ‘safety valve’ to ensure that the auditors can operate in an independent and objective fashion, but also ensures that significant issues can be raised between meetings.

It is more likely that the non-executives will meet, in other fora, with their executive director colleagues, and therefore may receive one side of an argument (see chapters 9 to 11 on handling disagreements), so the ‘independent and objective’ role of the non-executives need this balance.

With the right of access comes responsibility to use the right carefully. Auditors should not over-use the right, nor should non-executives use this to undermine their relationship with management.

Clearly, when an auditor asks for a meeting with the audit committee chair, this should be seen as a significant matter and the chair should seek a timely meeting, respecting confidentiality. How they handle the results of the meeting will depend on the matter raised.

Key learning points

Audit committee members should have some time to meet on their own to review agenda items and important discussions.

At least once a year, the committee should meet with external audit, internal audit and the local counter fraud specialist (jointly or individually) to ensure that they can speak freely.

Outside the formal meetings, auditors and the local counter fraud specialist have a right to access the committee chair, which should be used when other routes have been exhausted.

Chapter 6: Committee effectiveness

Overview

As is good governance practice, the audit committee should carry out an annual effectiveness review. There are a number of tools available to assist in this process, to ensure that the committee has met its terms of reference and been effective in achieving its overall purpose.

6.1 Good practice requirement

It is good governance practice for boards and their sub-committees to carry out a review of their effectiveness on an annual basis, with the option to use external assessments on a three or five year cycle to provide an added degree of independence.

Any review of effectiveness should seek to ensure that the committee is meeting its terms of reference and, in particular, its duties and responsibilities with regard to the oversight of a robust system of governance, risk management and control.

For a review of effectiveness, it is important that, while using best practice models as a basis, any review is adjusted to ensure that it is appropriately tailored for the NHS organisation and the specific issues that it covers such as working within an integrated care system (ICS), the importance of the freedom to speak up, the patient safety agenda and challenging financial climate.

Where the audit committee works with, or relies upon, other committees, it should consider specific questions about these relationships. These are most often based around the completeness and effectiveness of assurance on assigned board assurance frameworks or strategic risks.

One of the reasons for inviting the chair of the board to attend an occasional audit committee meeting is to feed into the chair’s wider understanding of how the overall governance arrangements are working in practice, and they can then provide their own impressions on the audit committee’s effectiveness, including that of the audit committee chair.

6.2 Use of checklists

To assist the audit committee in its review, the usual practice is to ask members and attenders to complete a self-assessment against a standard checklist. These can range from generic ones used within their organisation, to more ‘industry wide’ checklists that are NHS specific (see examples in appendix B) to some bespoke checklist that might come from good practice (for instance the National Audit Office (NAO) checklist toolkit for central government

Sometimes the completion of the checklists can be seen as burdensome, and there may be value in a two-stage report; for instance that the audit committee chair and secretariat complete the sections that cover the more ‘administrative’ elements of the committee, thus leaving the members and attendees to provide more qualitative feedback.

For some of the checklists the assurance may come from simple yes/no responses to ensure that the committee is covering standard practice. In others there can be more value in a scoring system across a range, in terms of the level of effectiveness. Wherever possible it is most helpful if comments can also be collected, both in support of good points, as well as how areas for improvement can be developed.

The collation of the results of the checklists should be undertaken by the secretariat and the committee should discuss prioritisation of any improvements.

6.3 Elements of an effective audit committee

While checklists can be useful in ensuring that the audit committee is generally compliant with its terms of reference, an effective audit committee is probably more about the conduct and behaviour of the members and attendees. A number of professional bodies set out traits of an effective audit committee including the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC)

Questions to consider on assessing effective audit committee behaviours:

Key learning points

Reviewing the effectiveness of the audit committee is an annual exercise required to ensure good governance.

A number of checklists are available to help guide the review, but attention should be given to matters that are specific to NHS organisations.

Effective audit committees are not just about fulfilling their terms of reference, but also about the culture and behaviour of the committee, and how it achieves its overall purpose.

Chapter 7: Committee reporting

Overview

The audit committee needs to report to the board (and other committees) on the most significant issues that it has covered on its behalf, so that all board members are aware of what is being done. The work of the committee needs to be summarised, on an annual basis, to support the annual governance statement.

7.1 Reporting to board

The audit committee’s work should be aligned to the board’s agenda, consequently its in-year reporting to the board is vital. After each audit committee meeting the audit committee should report to the board, drawing attention to the important issues discussed, and raising any matters requiring attention such as new risks, new assurance and progress with actions to close gaps in control or assurance.

While this can be achieved by a copy of the minutes (if appropriate for public or private board), it is probably more effective if the key points for the board’s attention are included in a summary report from the committee chair. Given the audit committee cycle of meetings, waiting for approved minutes may make reporting by minutes untimely.

Reporting to the board on the annual report and accounts should be an opportunity for the chief finance officer (CFO) and audit committee chair to emphasise the board’s overall responsibility for the truth and fairness of the report and accounts. While detailed scrutiny may have been delegated to the audit committee, it does not remove that ultimate responsibility from the board, and some form of challenge and review from the board would still be expected.

7.2 Reporting and liaising with other committees

It is unlikely that the audit committee will report to any other committee in the organisation, but matters may arise at the audit committee that were either directed to the audit committee to discuss (for instance the results of some form of external assurance), or where the audit committee may wish to direct a matter to another committee (for instance assurance on the oversight of particular risks or an internal audit review on patient safety to the quality committee).

It would be usual for the secretariat to arrange this reporting, as part of any action log, ensuring that the actions were followed up and completed.

7.3 Annual report in support of the annual governance statement (AGS)

In signing the AGS, the chief executive officer (CEO) will normally include a statement on their reliance on the audit committee for certain matters.

This is best met by the requirement for the audit committee to provide an annual report, in support of the annual governance statement, that aligns with the committee’s responsibilities and duties set out in its terms of reference. The report should look to provide an overview that:

the organisation’s system of risk management is adequate in identifying risks and allowing the governing body to understand the appropriate management of those risks

the committee believes that the assurance framework is fit for purpose and that the ‘comprehensiveness’ of the assurances and the reliability and integrity of the sources of assurance are sufficient to support the governing body’s decisions and declarations

there are no outstanding areas of significant duplication or omission in the organisation’s systems of governance that have come to the committee’s attention.

In addition, the report should highlight the main areas that the committee has reviewed and any particular concerns or issues that it has addressed.

These could include:

the reliability and quality of the organisation’s financial reporting systems that sit behind the financial position reported to the governing body

any significant issues that the committee has considered in relation to the financial statements

any major break-down in internal control or crystallisation of risk that has led to a significant loss in one form or another

any major weakness in the governance systems that has exposed, or continues to expose, the organisation to an unacceptable risk

an assessment of the performance of the external auditor and other assurance functions.

This is not a definitive listing and the audit committee will want to summarise the work that it has carried out, the topics that it has delved into and how it has used the work of the auditors. The report should not just focus on process and the number and type of assurances considered during the year, but include the outcome of the committee’s work, its conclusions and actions taken.

The report should not be long (three or four pages should be sufficient) and may be drafted by the committee’s secretary under the direction of the committee’s chair. The committee chair should take overall responsibility for the report’s preparation and share drafts of the report with committee members.

A first draft of the report should be produced promptly after the year-end, so that the major themes can be captured and fed into the AGS. The report can then be finalised later, to reflect such events as the completion of the external audit, receipt of the head of internal audit opinion, and so on.

Key learning points

The audit committee needs to report to the board on the most important issues that it has discussed.

The audit committee needs to report to, and be reported to, by other committees that it works with to ensure that there is appropriate and proportionate oversight between the board and its committees.

An annual report should be produced by the committee, in support of the AGS, on how it has met its terms of reference over the previous year, and highlighting the significant matters that it has discussed.

Chapter 8: Annual report and accounts

Overview

The committee undertakes the detailed review and scrutiny of the annual report and accounts on behalf of the board, using its independence and objectivity to ensure that they present a true and fair view. The committee will focus on areas of significance and risk, as well as receive a report from the external auditor.

8.1 Role of the committee

Responsibility for preparing the annual report and accounts rests with the full board and the chief executive officer (CEO) as accountable officer. As set out in HM Treasury’s Managing public money

While the preparation of the annual report and accounts is a management responsibility, the audit committee plays a key role in seeking assurance that there is an effective timetable (agreed by all parties), with proper co-ordination across the multiple stakeholders, to ensure that the document is brought together completely and accurately, and within time.

The audit committee’s role is to review the annual report and accounts, together with assurances from management, external audit, internal audit and other governance committees, before they are submitted to the board for formal adoption (and council of governors for NHS foundation trusts). Usually this involves considering a report from the chief finance officer (CFO) in April or May that highlights particular points of interest, explanation of significant variances from the prior year and in-year forecasts, and any areas that are under discussion with external audit.

However, where there are significant accounting matters (such as complex or large accounting matters, changes to accounting and reporting standards or significant new commitments or changes to service delivery), these need to be discussed at the audit committee well before the year-end, so that the full implications are worked through, and areas of potential disagreement identified and a plan put in place.

The committee will also consider a ‘report to those charged with governance’ from the external auditor (referred to as the ISA260 report - see chapter 10), that sets out the audit risks to the accounts, how these have been addressed and the findings from the audit.

8.2 Annual accounts

Detail on the annual report and accounts is included in HFMA’s Introductory guide to NHS finance

The audit committee’s review of the accounts is an important step in the governing body’s approval process and provides an opportunity for constructive challenge and scrutiny of the organisation’s financial information and the systems of control that produce it. Accordingly, committee members need to be able to understand the annual report and accounts before recommending their approval.

When reviewing the accounts, the committee may wish to pay particular attention to the following:

compliance with relevant requirements

the going concern assessment

changes in accounting policies and any deviation from the Group accounting manual (GAM)

Department of Health and Social Care, DHSC group accounting manuals, February 2024 changes in accounting practice due to changes in accounting standards

changes in estimation techniques

significant judgements made in preparing the financial statements

significant adjustments resulting from the audit

any unadjusted misstatements in the financial statements

explanations for significant variances

consistency between the financial outturn and the month 12 management accounts

any letters of representation.

The HFMA’s briefings, How to review and scrutinise the numbers during the year

8.3 Annual governance statement (AGS)

In addition to the financial statements, the part of the annual report that is particularly relevant to the work of the audit committee is the AGS. The AGS focuses on the stewardship of the organisation and draws together position statements and evidence on governance, risk management and control, to provide a coherent and consistent reporting mechanism. The HFMA’s Introductory guide to NHS finance

In reviewing the AGS the committee should be seeking consistency of its understanding of governance within the organisation with the public declaration included within the AGS.

The AGS must be set out in line with the GAM issued to NHS organisations each year, as well as specific requirements for NHS foundations trusts in the NHS foundation trust annual reporting manual (FT ARM)

The key areas covered include:

scope of the organisation’s accountable officer’s responsibilities

information about the organisation’s governance framework

a description of how risk is assessed and managed

information about how the risk and control framework works

a review of the effectiveness of risk management and internal control

a review as to how well resources have been used

any significant risks and how they are being addressed.

Issues that the committee may wish to consider are:

whether the statement includes all the elements required in relevant guidance

whether there are any inconsistencies between the statements made and reports the committee has received from auditors or other sources of assurance

whether any significant control issues or gaps in control or assurance recorded in the statement are consistent with reports the committee has received

whether the statement gives a balanced view of the organisation’s governance arrangements over the last year.

The committee should also consider the annual head of internal audit opinion (HoIA)

The committee will then report to the governing body confirming that the draft AGS is consistent with the view of the committee on the organisation’s system of internal control and that it supports the governing body’s approval of the statement, subject to any reasonable limitations that the committee may draw attention to. To be able to carry out this review effectively, the audit committee will wish to look out for any possible problem areas or gaps throughout the year and discuss them as they arise.

8.4 Accounting policies and judgements

The annual report and accounts of NHS organisations are bound by the Financial reporting manual (FReM)

A key area of focus, for management, auditors and the committee will be on areas where these policies have changed or can have different interpretations. Before the year-end (see example agenda and timetable at appendix C), the committee should review the proposed accounting policies, in particular any new or amended ones, understanding the implications of the change and gaining assurance that management and auditors have a plan in place.

In recent years, some changes in accounting policies have had significant resource implications, such as IFRS 16 on lease accounting. The committee should be assured that a realistic plan is in place to comply with any new accounting standards issued and their impact on the financial position of the organisation.

There will also be areas where judgements will be needed, either because accounting policies are not prescriptive, or the area is inherently uncertain. An example of this might be over the likelihood of legal cases being successful and so requiring a level of provision. Where these are material (see glossary at appendix D), it is important that the process to make judgements is agreed in advance, is consistent year on year and has some form of challenge to avoid bias. The audit committee can have a role in reviewing the process and discussing any differences between management and auditors.

8.5 Annual report

The terms of reference note that, in reviewing the annual report and accounts, the committee will focus on certain areas that are closest to its terms of reference, but the committee is still reviewing the annual report in advance of the board and should therefore cover the full annual report.

The size of annual reports have increased over recent years and contain a whole range of information; from workforce data to environmental measures, patient activity and outcomes measures. The committee should seek assurance that the compilation of the annual report has been carried out in a managed manner, and should have its attention drawn to any areas of particular sensitivity.

Given the independence of the non-executives, and their wider knowledge, they should look to ensure that management have given a balanced review of the year gone by, avoiding over optimistic interpretation of the results or omission of significant matters.

8.6 Logistics of delivering the annual report and accounts

NHS organisations are required to follow a timetable for submitting both draft and final audited accounts that is set by NHS England

In recent years, this timetable has required draft submission by late April and final audited submission towards the end of June, in other words within three months of the end of the financial year.

To achieve this requires very detailed planning by management and auditors, with the audit committee seeking assurance – from both parties – that there is an agreed and detailed understanding of each parties needs, a jointly developed and deliverable timetable and plan, an escalation procedure and strong relationships in place.

Early sight of issues that may result in delays is important, and both the CFO and the external audit representative should keep the committee chair up to date on developments.

Anything that emerges after the audit committee has reviewed the accounts, or is a matter that the audit committee only agrees the accounts ‘subject to’, needs to be communicated to the audit committee members, not least so that they can assure their fellow board members when it comes to the formal approval.

8.7 Quality accounts

In prior years some elements of the quality accounts were subject to external audit review (see chapter 10), but this ceased during the Covid-19 pandemic and is unlikely to recommence as a mandated requirement.

Oversight of the quality accounts will usually be delegated to any quality committee, but the audit committee may work with that committee to seek assurance on data quality of key indicators, potentially as part of any internal audit plan, as well as reviewing consistency between the quality accounts and the annual report and accounts in relation to quality and performance reporting.

Key learning points

The audit committee undertakes the detailed review and scrutiny of the annual report and accounts on behalf of the board, but does not take responsibility away from the full board.

The audit committee focus will be on the elements of the annual report and accounts covered by external audit, such as the financial statements, remuneration report and AGS, but the committee should ensure that the wording in the full annual report is consistent with their understanding.

The focus of the audit committee will be on the areas of greatest significance and risk to the truth and fairness of the financial statements such as accounting policy changes, judgements and estimates.

A particular focus will be the wording in the AGS.

Delivering the final signed and audited accounts will require careful planning and timetabling.

Chapter 9: Internal audit

Overview

Internal audit provides objective assurance, following Public sector internal audit standards (PSIAS)

9.1 Role and regulation

The Institute of Internal Auditors define internal audit as providing:

'An independent, objective assurance and consulting activity designed to add value and improve an organisation’s operations. It helps an organisation accomplish its objectives by bringing a systematic, disciplined approach to evaluate and improve the effectiveness of risk management, control and governance processes'.

The Institute of Internal Auditors, Definition of internal auditing, January 2024

There are two clear roles from this definition: assurance and consultancy. For the audit committee the focus of its attention will tend to be on the assurance role, but there are many opportunities to use the skills, knowledge and experience of internal audit to support management in the improvement of governance, risk management and control. However, the blend of the two needs to be carefully balanced, as well as ensuring that there is no conflict between the work internal audit undertakes (in other words it cannot audit an area that it has previously advised on).

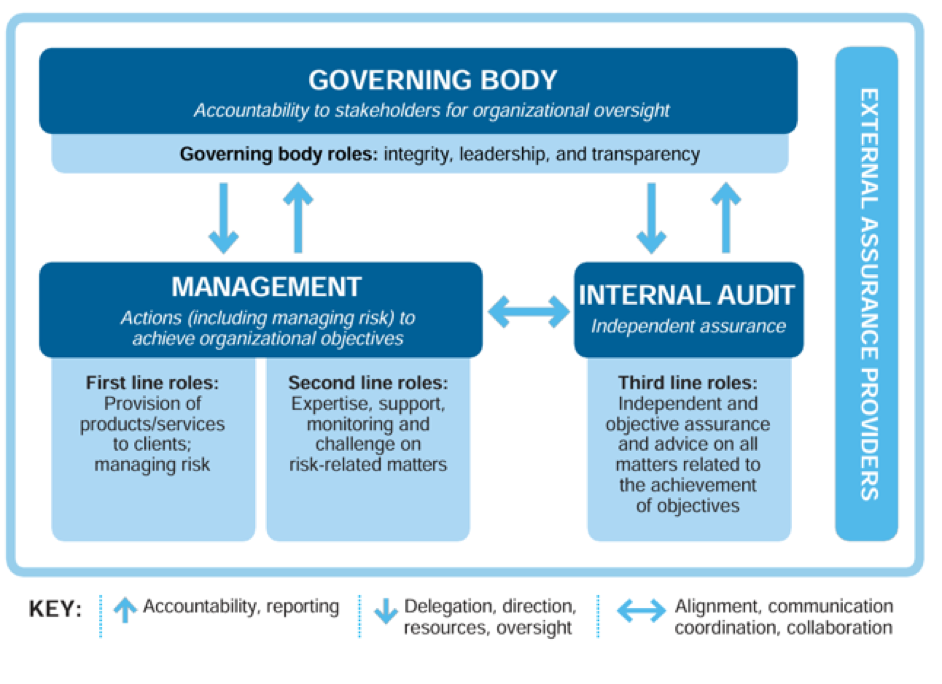

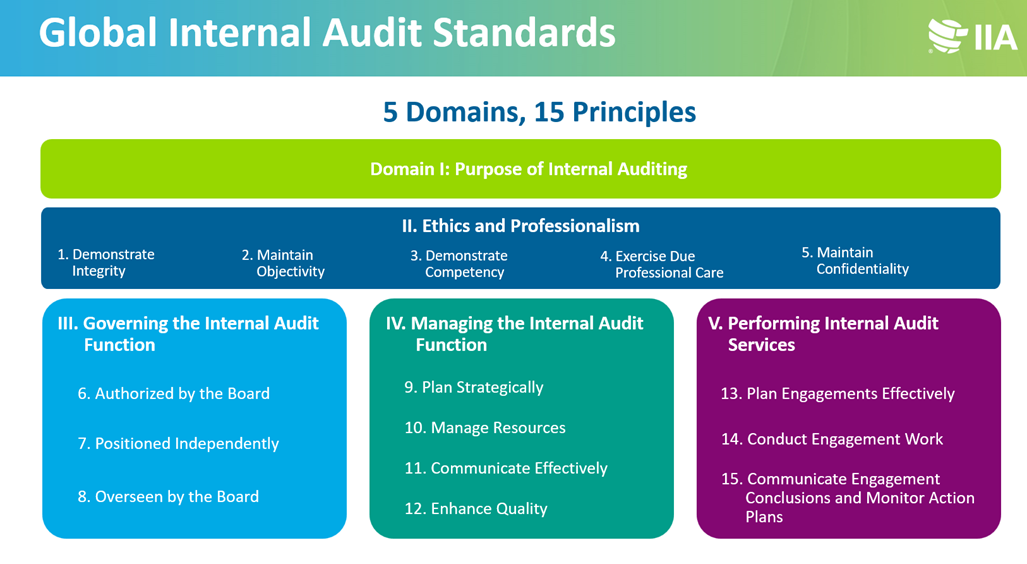

All public sector internal auditors are required to follow UK PSIAS. The PSIAS are based on standards issued by the Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA), with additional requirements and interpretations to make them applicable to the UK public sector. In January 2024, the IIA announced the release of Global internal audit standards (GIAS)

The current standards set out:

the mission, definition and core principles of internal audit

code of ethics

attribute standards (for example, purpose, independence, proficiency, quality assurance)

performance standards (for example, planning, performing, communicating).

Central government has adopted a number of functional standards

On appointment, and reviewed regularly, there should be an agreed internal audit charter that sets out the authority and responsibilities for internal audit, both for the internal auditors as well as management. This charter should be agreed by the audit committee on behalf of the organisation.

9.2 Appointment and tendering

While some internal audit teams are in-house, the majority are delivered by either NHS, not-for-profit consortia or private sector firms. There is therefore a market for internal audit services and the audit committee will need to evaluate the internal audit delivery and assess its effectiveness and, where outsourced, be involved in the tendering and contracting for internal audit services.

Unlike external audit (see chapter 10), where the role and requirements are very specific, the nature and extent of internal audit coverage is more open to interpretation. The organisation, through its audit committee, should clarify its assurance requirements (see chapter 15) to help direct the requirements and expectations from internal audit.

When tendering, the service specification sent out to tenderers is an important document to set out the organisation’s requirements.

In developing this there needs to be consideration of:

the desired level of assurance required by the organisation, on the basis that the lowest proposed audit plan may not be the most appropriate

quality and mix of staff that would be available, in terms of skills and experience (including specialists in such areas as NHS clinical systems, IT or project management)

suitable key performance indicators

breadth and depth of coverage taking into account other sources of assurance

consistency with the audit committee’s terms of reference and working practices

comparison to current charter and plan.

While the detail of the service specification will be drafted by management, the audit committee should have a role in reviewing it before finalisation. While tendering will often be off framework agreements, it is important that any specification is suitably tailored to reflect specific needs.

9.3 Planning

The internal auditors should produce an overarching strategy on how they will fulfil their role, from which more detailed operational plans should follow. The standards require a three-year plan (generally indicative) and an annual plan (which will change), while there are moves to consider more flexible plans (from 15 month rolling plans to six monthly). This strategy, and resulting plans, should be agreed by the committee. The plan should be flexible and reviewed by the audit committee quarterly to ensure it remains focused on the organisation’s assurance needs.

In undertaking their planning, the internal auditors should include:

a risk assessment of the external environment, system and organisation (including the board assurance framework)

consideration of previous internal audit coverage

engagement with the audit committee, executive directors and management

coverage of critical business systems (such as core financial systems and those that ensure compliance with legislation and requirements, deliver key services or support the delivery of business objectives).

Professional standards require that the internal audit plan should be risk-based, designed to provide independent assurance focused on the principal risks of the organisation. Part of this can be achieved by internal audit reviewing the system of risk management, to ensure that it is effective in identifying, assessing and reporting on the management of risks (see chapter 14).

The audit committee will need to ensure that individual audit assignments are appropriately focused on principal risk areas, particularly those that are being reported by management as not being effectively managed. Assignments should review arrangements in place for ensuring appropriate risk management (by design and operation) is in place and that the risks are being effectively managed.

The planning process is ultimately designed to allow the head of internal audit (HoIA) to provide an annual opinion in support of the annual governance statement (AGS). This would suggest that some critical areas would be subject to annual review (for example, the system of risk management), others within a rolling long-term cycle (for example, individual financial systems), while others are audited due to particular issues (for example, individual major projects at key stages of their life). There have been instances where audits have been mandated by NHS England (for example, financial sustainability) or there is a contractual need (for example, data security protection toolkit).

The potential areas that internal audit might review are numerous and are commonly known as the internal audit universe.

These cover a range of specific areas of focus within overriding themes such as:

governance

clinical and patient safety

quality and performance

financial control

information management and technology

human resources and workforce

estates and facilities

commissioning procurement and contract management.

These are indicative areas and no strategy or plan could hope to cover them all, so a process of prioritisation will be needed. Internal auditors will undertake a risk assessment which brings together all the potential areas for internal review and these are then subject to a process of prioritisation for inclusion within the operational plan.

The audit committee needs to satisfy itself that the planning process is robust. This should include discussion with key executives, input from the audit committee, liaison with other assurance functions to avoid duplication and with external audit to ensure coordination with their work.

9.4 Reporting

At the end of each internal audit assignment, the findings of the audit should be reported to management, including an overall opinion on the effectiveness of the arrangements in that area (in terms of the governance, risk management and control arrangements) and recommendations or agreed actions for improvement.

The audit committee does not necessarily need to see the full detail of every internal audit report, although it may be appropriate for the chair of the committee to be copied into them. However, each committee meeting should, as a minimum, receive a summary of each report within a progress update from the internal auditors.

Where audit reports are assigned an adverse opinion rating (such as ‘limited’ or ‘unsatisfactory’) then the audit committee will want to review the findings in detail. These reports should be a separate agenda item, where the executive lead should attend the meeting to explain their position and provide assurance regarding the actions that they are taking to address the issues raised. The audit committee needs to be satisfied that the actions being taken by management are sufficient and timely enough to address the auditor’s findings and will succeed in ensuring that the area will be effectively managed.

At the end of the year the HoIA will produce an annual report and opinion

This report should set out the work undertaken in the year, summarise the results of that work and give the overall opinion on the effectiveness of governance, risk management and control. Providing a thematic analysis of internal audit results within the annual report can also be useful for committee members. The final annual opinion level (see 9.6 below) needs to be considered by the committee, in terms of the rationale for the opinion and the direction of travel, whether or not there is a positive or negative move year on year. It is important that the audit committee appreciates that the opinion is a judgement, rather than a calculation, and is based on an assessment of a range of factors; from the assurance framework, risk management system, results of individual assignments to management’s response to internal audit work.

9.5 Implementing agreed actions

The implementation of agreed actions arising from internal audit reports (indeed arising from any report) is a key focus for the audit committee, meeting a couple of needs:

it can demonstrate whether, or not, management take internal audit and the need for assurance seriously, as well as whether there is an understanding of risk management

it can demonstrate whether management actions responding to issues being highlighted by internal audit are pragmatic solutions (as opposed to textbook answers).

In particular, the audit committee will want to review the timeliness and completeness of the management actions, and that they have been effective in improving the management of risks. If the action has been agreed, and it is based upon a risk not being managed effectively, then the longer that the action takes to implement, then the longer the organisation is exposed to that risk.

In some instances, it is perfectly right for management not to address an issue reported by internal audit. In these instances, management may believe that the cost of the additional controls outweighs the benefits, and therefore they are prepared to accept the risk. They may, alternatively, disagree with internal audit on the risk involved or believe that compensating controls are sufficient. Where this situation arises then it is the audit committee’s role to independently consider the issues and whether they concur with management’s assessment, or request that they reconsider their response.

9.6 Opinions

While there has been some effort to try and standardise opinion levels, the terminology and ratings in use differ between providers. In 2020, CIPFA

Internal audit engagement opinions, based on CIPFA definitions:

Other examples may use different terminology but tend to have a similar number of categories. For example, the Government Internal Audit Agency uses: ‘substantial’; ‘moderate’; ‘limited’; and ‘unsatisfactory’

It is important to remember these ratings are not presented as a ‘statement’ or ‘fact’, but are called ‘opinions’ for a reason. They are a judgement determined by the HoIA, and it is often not a simple binary decision. This can often be a source of contention between management and auditors.

The audit committee will need to understand the logic behind the opinion. Where opinions are disputed the committee can give useful feedback on whether the issues and rating assigned are consistent with the control environment and risk appetite expected by the organisation.

9.7 Handling disagreements

As with any audit function there will inevitably be occasions where auditors and management disagree. This is where the audit committee brings its independent and objective judgement to bear.

Most disagreements should be resolved through the normal audit process; from agreeing the scope of work at the planning stage, evidence review during fieldwork, discussions around the initial findings and agreeing the final report, including management response and agreed actions.

Where significant disagreements cannot be resolved, the HoIA should use their right of access to the chair of the audit committee to raise the matter, confidentially if needs be. As a matter of routine there should be regular time scheduled (at least annually) either before or after audit committees for the committee to meet auditors privately without management present. This time can be useful to help identify and address any problems being experienced by internal audit.

9.8 Reviewing effectiveness

At least annually the audit committee, without the internal auditors present, should consider the effectiveness of the internal audit service.

For this the committee should:

consider whether they have been satisfied with the quality of work seen (for example, the breadth, depth and timeliness of work reported)

seek opinions from the lead executive (usually the chief finance officer (CFO)) and from other senior management who have regular involvement with them (for example, the director of governance or trust secretary)

review performance against agreed key performance indicators

review the results of any internal quality assessments by the internal audit provider and the five yearly external quality assessment

take into account other evidence available, such as added-value briefings supplied and the results of any post-audit feedback from management.

Where there are concerns about performance and effectiveness they should be raised with the HoIA and an improvement plan agreed. This plan should be monitored by the lead executive responsible for the service (usually the CFO).

The IIA’s report Harnessing the power of internal audit for audit committees includes eight key areas the audit committee may wish to consider in reviewing its internal audit arrangements.

Key learning points

Internal audit is about both assurance and consultancy.

Internal auditors work to public sector internal audit standards and adopt a risk-based audit plan.

The committee will be involved in the tendering and appointment of internal auditors and should understand the scope of work that is required.

The audit cycle runs from an overall strategy, through an annual plan and individual assignment reporting, to an annual report in support of the annual governance statement.

The way that management reacts to internal audit reports, particularly in the implementation of agreed remedial actions, is an important indicator of the importance given to this function.

Chapter 10: External audit

Overview

NHS organisations must appoint their own external auditors to provide an opinion on the financial statements and commentary on value for money (VFM) arrangements. Non-executives have a key role in selecting, appointing and managing these contracts. The work of external auditors must be carried out in accordance with professional requirements, standards and guidance, which shape the audit work from initial planning through to reporting.

10.1 Role and regulation

The external audit of an NHS organisation is required by law (Local Audit and Accountability Act 2014 and NHS Act 2006)

forming and expressing an opinion on whether the financial statements are prepared, in all material respects, in accordance with the Group accounting manual (GAM)

Department of Health and Social Care, DHSC group accounting manuals, February 2024 to be satisfied that the VFM arrangements that the organisation has in place to secure economy, efficiency and effectiveness in its use of resources are working and to include a commentary (and associated recommendations) in their auditor’s report on financial sustainability, governance and improving economy, efficiency and effectiveness. Where auditors identify significant weaknesses in arrangements as part of their work, they should raise them promptly with those charged with governance

reporting on regularity (ICBs only)

considering whether to exercise statutory powers such as a report in the public interest, written recommendations to the audited body (ICB and NHS trust only) or a referral to the Secretary of State.

The Code requires auditors to follow International standards for auditing (ISAs) issued by the Financial Reporting Council (FRC)

Further detail on external audit reports and auditors’ additional powers and duties is set out in the HFMA’s briefing, External audit reports: the role of the audit committee

In recent years, following corporate financial reporting failings, external audit firms have been under increasing regulatory pressure from the FRC and the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW) to improve audit quality. This has led to a strengthening of the ISAs, which, in turn, has led to an increased amount of audit work and greater assessment of evidence.

Each year, the FRC publishes its inspection findings into the quality of major local body audits in England

10.2 Appointment and tendering

All NHS organisations have a statutory responsibility to appoint an external auditor, albeit there are differences in the underlying legislation for ICBs, NHS trusts and NHS foundation trusts.

NHS trusts and commissioners

The Local Audit and Accountability Act 2014 (LAAA)