Feature / One to one

Improved arrangements for enhanced nursing care – or specialling – can deliver patient benefits and save money. Steve Brown looks at how two trusts have shown the value of a more structured approach

Improved arrangements for enhanced nursing care – or specialling – can deliver patient benefits and save money. Steve Brown looks at how two trusts have shown the value of a more structured approach

Lord Carter’s preliminary report of NHS productivity identified specialling – or one-to-one nurse care – as an area where greater consistency could improve care and reduce costs. A number of NHS providers have started to realise these benefits, but there is significant scope to expand this best practice across the service.

There are definitely savings to be had – Lord Carter’s report suggested that Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust, which has pioneered some of the improvement work in this area, was anticipating trust-wide savings of more than £1m a year based on its results in the first few months operating a new system. But financial savings – many of which arise from reduced usage of bank or agency staff (where trusts continue to face extreme cost pressures) – are just part of the benefits package.

Improved specialling arrangements can also help deliver more consistent, patient-centred care and greater involvement of patients’ relatives and carers, and provide nurses with more support to take key decisions about patients’ requirements.

East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust is one trust to have made major progress following Salford’s initial example. It was one of 12 providers to work with the former NHS Trust Development Authority to attempt to replicate Salford’s work using a Lean management 90-day rapid improvement programme.

The hospital trust’s quality improvement facilitator, Sonia Nosheen, says the trust was operating in the dark with specialling when it joined the TDA initiative. ‘It was difficult to know how much we were spending,’ she says. ‘Everyone had a different opinion on how the process should work. And we didn’t even have a clear definition about what one-to-one care meant across the organisation, sometimes confusing it with other forms of enhanced care such as cohorting.’

Although the trust only had a loose grasp on what it was currently spending on specialling, it recognised that costs were rising and that there was significant potential for improvement. However, data issues added to the problem. Its e-rostering system at the time was set up in a way that, depending on what other data was being entered, it was not always possible to record enhanced care; and it was not possible to distinguish between, for example, one-to-one care and cohorting (patients requiring observation, often with a 1:4 ratio).

Even if it relied on its data as accurate, there were further difficulties in interpretation. Nurses had traditionally used gut instinct, informed by their experience, to identify patients who needed enhanced care. But this made it difficult to understand changes in the incidence of specialling over time. For example, the trust could see a major step change in use of specialling – but it was not clear what might be behind this.

There had been a couple of serious incidents around the time of the increase. But there was also new guidance on mental health enhanced care that could have influenced acute practice. The hike could equally have been influenced by changes in personnel or casemix. Without a consistent and robust process to put specialling in place, there was simply no way to understand the changes.

All 12 trusts in the TDA cohort implemented changes in their approach to specialling. At East Lancashire, the trust piloted changes on three wards covering older people, complex care and orthopaedics.

With the 90-day programme broken into three 30-day report back sections, the trust went through a number of plan-do-study-act cycles to improve different components of the overall process.

First it tackled its data problems, recognising that robust coding was essential to better management of enhanced care and to demonstrating the impact of changes. Its e-roster system, through which all requests for enhanced care are made, now enables all cases of enhanced care to be recorded and the different levels of care separately identified.

Its next step was to explore how it could involve relatives and carers more – both to understand better the quality of care for vulnerable patients and to explore how relatives could be more involved with care where they wanted to do so.

Ms Nosheen said feedback to a survey underlined that relatives were often keen to be more involved and that this had benefits for patients and could reduce demands for enhanced care.

In order to take this forward, the trust worked with John’s Campaign, which aims to give the carers of those living with dementia the right to stay with them in hospital.

‘We want to give holistic care, but we want to work in partnership with the relatives and carers, so it is really important when a person comes in, and they are assessed by the nursing staff on the ward, that we get a history from the patient,’ says Jarrod Walton-Pollard, director of nursing for the surgical division. ‘This means we can understand their needs – do they want to spend more time with their loved one or have open visiting? Or perhaps they want to have a rota with all the family and carers so someone can be with them all the time.’

This has led to the development of material both to support nursing staff in discussing the option of family/carers providing informal one-to-one care and to help explain the options to relatives.

Implementing changes

Next on the ‘to do’ list was to provide more support to nursing staff on what was expected of them in one-to-one care. ‘One-to-one care is also about engaging with patients and getting to know them as well as monitoring them,’ says Ms Nosheen. ‘This has therapeutic value.’

Nurses are now issued with nurse pocket cards detailing a set of rules to be observed during one-to-one care. Nurses are also required to log activities and this log is passed from one care giver to the next.

The final step was to put the whole triggering of enhanced care onto a more robust footing. Salford had developed its own risk assessment checklist to support the specialling decision-making process.

Ailsa Brotherton, clinical quality director for the North at NHS Improvement, who led the TDA’s support for trusts on specialling alongside nursing director Peter Blythin, says practices across the cohort of 12 trusts varied. Some had no risk assessment in place, and where they did exist there were differences in the quality and how they were used.

‘Some were not very robust. They provided a simple checklist – had the patient had a fall for example – but gave no indication of what to do if they had,’ she says.

Having looked at various risk assessments already in use, the cohort of trusts opted for one developed by University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, which incorporates a clear scoring mechanism that links to different levels of enhanced care.

‘Nurses really liked the mechanism,’ says Dr Brotherton. Not only did it help them make an important decision on the level of care needed, but it created an audit trail for the decision-making process.

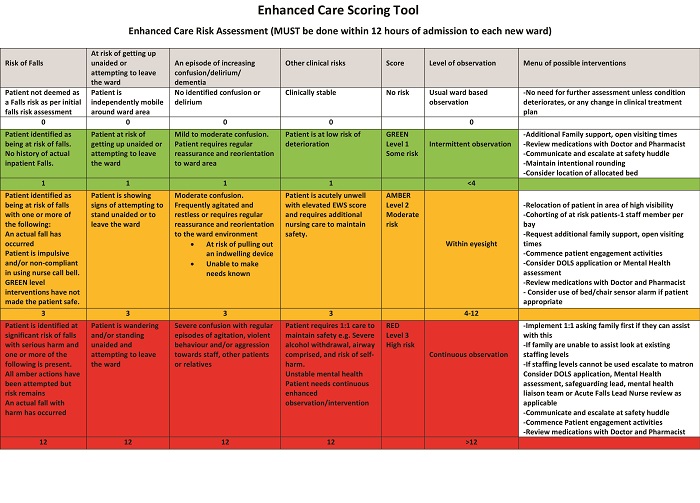

East Lancashire was one of the trusts that did not have a pre-existing risk assessment in place and has adopted the UCLH template with a few minor tweaks to suit its local context. Patients are scored in four key areas:

- Risk of falls

- At risk of getting up unaided or attempting to leave the ward

- Increasing confusion/delirium/dementia

- Other clinical risks.

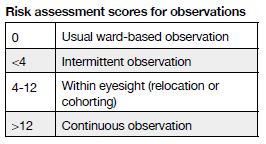

Each patient is assigned to one of four levels in each of these areas – representing no risk (white, score 0), some risk (green, score 1), moderate risk (amber, score 3) and high risk (red, score 12). Once a patient is assessed, the individual scores are summed and the total indicates the level of observation needed.

This simple tool (above) includes prompts to help nurses assign patients to the relevant level in each risk area and also reminds nurses of possible interventions associated with each observation level. Risk assessments are carried out on all patients (aged 18 upwards) within 12 hours of admission to the ward. However, the trust has also put in a structure around reassessments. Its new standard operating procedures state that the level of enhanced care for any patient must be reviewed on an ongoing daily basis and reviewed at the start and finish of each shift by the nurse-in-charge. Decisions to discontinue enhanced care are documented in medical and nursing notes.

‘When we asked trusts about their specialling policies we were sent lots of information about how and when to start specialling, but very little on how to stop it,’ says NHS Improvement’s Dr Brotherton.

‘In many cases, once specialling started, it never stopped until a patient was discharged. But patients’ conditions and needs change and there are some potentially big wins here while still ensuring care meets patient needs.’

East Lancashire showed a significant improvement in the three-month pilot period. Its aim for the project was to improve quality and patient experience and reduce the cost of bank and agency spend by 20%.

In fact agency/bank spend to support specialling reduced by nearly £19,000 or 68% compared with the previous three months’ spend – more than three times the target reduction.

It is now rolling out the new process across the trust – which includes 50 wards. And it has also raised its ambitions, targeting a 50% reduction in the cost of agency and bank spend. If it achieves these savings across all its wards, it would be close to matching the £1m annual savings estimated as possible by Salford.

The roll-out involves raising awareness of the reasons for the programme and clear communication about progress. There is also a significant training agenda – both for substantive and temporary staff. This covers what is expected of staff when requesting or delivering enhanced care and talking to families and carers about the ‘partnership in care’ options.

Ms Nosheen believes the challenge is to ensure the new process is sustainable. As part of this, the trust is looking to use its internal nursing assessment programme to ensure the process is working and being adhered to. ‘What made this work was that cost wasn’t the driving force. Cost is important but the focus was on process and quality,’ she says.

‘However, what the pilot proved was that if we get the fundamentals of care, experience and quality right for our patients, then the costs move in the right direction.

‘This has to be sustainable and spreading it across the organisation so that we have the same standard embedded as daily practice in all areas is the key to making this successful in the long term. This will not be an easy task and will take time,’ she says.

‘But we are confident that, having successfully tested the interventions in the pilot wards, we will be able to make it an organisation-wide success. This is helped by the aims of the programme strongly connecting to the values of our staff and organisation to provide safe, personal and effective care.’

Risk assessment scores for observations

Patient focus: key to Salford improvement

Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust says improving care was the sole focus for changing

arrangements around enhanced care at the trust – and this was at the heart of the programme’s success.

However, there were significant financial savings from the outset and these have been sustained. The trust has rolled its revised practice out across its more than 40 wards and remains on target to realise the £1m of savings referred to in Lord Carter’s preliminary report on productivity improvement in acute hospitals.

Peter Murphy (right), trust director of nursing,

quality and governance, says there had been

an increase in demand for one-to-one care across the trust before it introduced its new system. The trust had up to this point considered this issue from a professional point of view – how best could it manage the increase in activity? This had led to the use of a pooled team of nurses in its neurosciences area dedicated to enhanced care duties.

The catalyst for change came when the trust tackled the issue from the point of view of the patient. One elderly patient was admitted for pneumonia, but also had been newly diagnosed with the onset of dementia. He talked about ‘feeling scared’ to wake up and find a stranger by his bed. His wife talked about being parted from her husband for the first time in years, going home and crying, wondering why she couldn’t be part of her husband’s care.

‘It was a lightbulb moment,’ says Mr Murphy. ‘You have to do what is right for the individual. Not how we want to professionally manage this situation, but how to approach it from a patient-centred point of view.’

The revised approach involved four key changes. The trust introduced a revised risk assessment process that provided a more rigorous basis for deciding when enhanced care was appropriate. It described different levels of increasing observation from co-locating patients in a bay, with a nurse or nurses looking after multiple patients, through to specialling. The risk assessment process produced scores that were linked to these different levels of observation.

It also introduced a requirement to talk to relatives or carers about how they might like to be involved in the care of the family member. And it added a requirement for a senior nurse to sign off any request for specialling.

Mr Murphy says that involving the family/carer with the care – referred to as triangulation of care – was the single most important change the trust made. He adds that the foundation for the programme’s success and its sustainability was that the changes were staff-led. ‘This was designed by staff and they are proud of the changes,’ he says. ‘When you own something, you are much more likely to practise it.’

Roll-out from the original four wards to the more than 40 across the trust was also relatively smooth and rapid. Link nurses from wards were trained in the elements of the change package. Within four weeks all departments then had to return a pledge card with signatures from staff indicating they had read and understood the principles of the change package.

Levels of one-to-one care are considered alongside other metrics at weekly ward-based dashboard meetings with ward managers. But to a large extent the new system has simply become normal working practice.

Mr Murphy says other trusts could benefit from taking a similar approach, although they would need to localise the process and ensure staff ownership of any changes. He also says that Salford is open to further refinements.

For example, the trust is using surveillance technology for some specific patient groups as a way to improve observation in certain circumstances. And it is keen to re-import any refinements to its process from other parts of the NHS.

In summary, he insists the changes are a no-brainer, delivering better care at lower cost. Indeed he says that savings started almost immediately with a significant fall in specialling budget before costs plateaued at a new lower level.

But he adds that the focus has to be on the care quality not the savings. ‘During the change package and all the work we did, we anticipated savings would follow, but we never once talked about money. We simply focused on putting a patient-centred approach in place that did the right thing first time around for individual patients.’

Efficiency map

The HFMA and NHS Improvement have been working together to update and revise the NHS efficiency map. This interactive tool, due to be published soon, supports best practice in delivering cost improvement programmes. The map signposts existing tools and reference material, bringing links to wide-ranging material into a single place. It is split into three sections – enablers for efficiency; provider efficiency; and system efficiency – and also includes updated definitions for different types of efficiency improvement. Case studies of existing good practice in cost improvement – including the ‘specialling’ case study produced here – are being developed to accompany the map.

Related content

We are excited to bring you a fun packed Eastern Branch Conference in 2025 over three days.

This event is for those that will benefit from an overview of costing in the NHS or those new to costing and will cover why we cost and the processes.