CCG allocations: fair shares

By its very nature, the formula used to allocate funding from NHS England to commissioners will always create relative winners and losers. Under long-established policy, areas of greatest need receive the biggest percentage increases. But, with the formula revised, a casual observer of the allocations for the next five years would be forgiven for thinking that even the ‘losers’ will be winners.

NHS England said every CCG would receive a minimum cash increase of 4.4% in 2019/20 and at least 17% cash over five years. The new allocation formula – which targets health inequalities and areas with higher early deaths – coupled with additional funding, appears generous, even at the lower end. But peel away the layers beneath the headline figures and CCGs will have a lot less flexibility in their spending decisions than it would appear.

NHS England set out five-year allocations overall, with the first three years’ funding finalised, and the remaining two issued as indicative figures. Announcing the allocations, the national commissioning body highlighted the 4.4% minimum rise in 2019/20. However, these figures appear to be referring to the total place-based allocations, which include core, primary care and specialised allocations. Generally, when analysing allocations, funding for the core CCG programme is used – the smallest percentage uplift in 2019/20 is 3.6%.

Overall core funding to CCGs will rise in cash terms by 5.65% in 2019/20, falling to 4.14% in 2020/21; 4% in 2021/22; 3.78% in 2022/23; and 3.54% in 2023/24.

Compared with other parts of the public sector, NHS funding remains relatively healthy, though it has to be remembered that large chunks of CCG allocations are already ringfenced. Funding to cover the increases in Agenda for Change pay awards will flow through the tariff for the first time in 2019/20 and £1bn of the Provider Sustainability Fund (PSF) will be transferred to the tariff for urgent and emergency care. Both funding streams are included in the uplifts above.

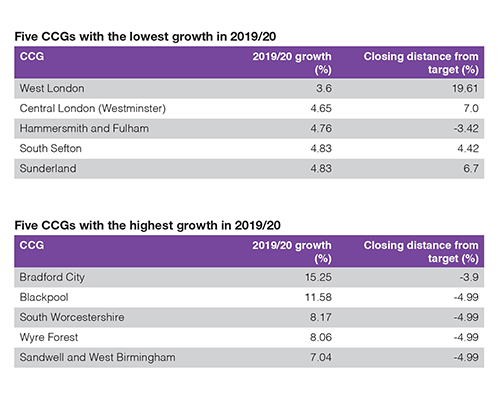

Once pay and PSF are stripped out, CCG programme growth falls from almost 5.7% in cash terms to 3.4% in 2019/20. In 2019/20, individual CCGs will see increases of 3.6% to 15.25% in their core funding (see tables).

Julie Wood, chief executive of NHS Clinical Commissioners, says funding will flow to those most in need. But she adds: ‘There remain considerable challenges in the short term for CCGs, with much of the additional funding already having been allocated nationally, leaving little for CCGs to allocate to local priorities. Over the five years of the increased funding, CCGs will need to find a balance between using this investment for new developments while making sure the NHS remains sustainable for the future.’

NHS England insists the new formula has protected long-term plan commitments to increase spending on cancer, primary care and mental health. And it says the new formula is highly redistributive – it expects £2.2bn to be redistributed within target allocations by the end of the five-year period. A major factor affecting CCG target allocations appears to be a shift to addressing areas with higher premature death levels. This is measured by the standardised mortality ratio in those under 75 (SMR <75), which is used as an indicator of health inequalities and unmet need.

NHS England interim chief finance officer Matthew Style told the commissioning organisation’s January board meeting that the additional weight given to the measure has led to little change for most CCGs. However, outliers on the SMR <75 measure, with higher rates of premature deaths, will see bigger rises.

NHS England said this change alone will increase Blackpool CCG’s core target allocation by 5.13%, or £16m, and overall it will receive the second biggest percentage uplift in 2019/20 (11.58%).Bradford benefits

Bradford City Clinical Commissioning Group is another beneficiary, with its allocation increasing by 15.25%, largely due to the change to address high rates of premature deaths. Bradford City chief finance officer and deputy chief officer Julie Lawreniuk said: ‘It’s really welcome, though I think a lot of people miss the huge inequalities we have in Bradford City. Our hospital usage is low, and we want to see it rise as we increase the awareness of the healthcare and prevention services that are available.’

Upping the population’s use of hospital services may seem to be going against the direction of travel – the long-term plan for the NHS in England instructs local health services to provide more care out-of-hospital. However, increasing hospital usage in Bradford City will be about earlier cancer diagnosis or intervention to limit the effects of other major killers, such as heart disease.

Upping the population’s use of hospital services may seem to be going against the direction of travel – the long-term plan for the NHS in England instructs local health services to provide more care out-of-hospital. However, increasing hospital usage in Bradford City will be about earlier cancer diagnosis or intervention to limit the effects of other major killers, such as heart disease.

‘We’ve had bits of non-recurrent funding in the past, but we see this as an opportunity to invest long-term in services and a permanent workforce,’ Ms Lawreniuk adds.

It’s early days and Bradford City CCG is reviewing its plans for the coming financial year. However, in the short-term Ms Lawreniuk believes the CCG will not be looking to develop new services – instead, it has evidence-based programmes ready to go or that can be scaled up quickly. These include Bradford beating diabetes, which helps those with type 2 diabetes stay healthy, and Bradford’s healthy hearts, which targets prevention of heart attacks and strokes.

Its cancer screening programme will play a big role as it looks to tackle the rate of premature deaths in the city. There is also a wealth of information from the Born in Bradford programme about pre-conceptual care that has already been evidenced through Better start Bradford – a range of programmes to support pregnant women and families with children under four.

‘I don’t think there will be a problem spending the money in 2019/20 and then recurrently. The challenge for us will be to ensure it makes a difference to the level of inequality in the city,’ says Ms Lawreniuk.

Other CCGs say their flexibility to spend their increased budgets has been limited by national spending commitments on pay, urgent and emergency care tariffs, mental health and primary care. However, due to the relatively large increase in its allocation, Bradford City will still have a good deal of flexibility to shape its spending plans, Ms Lawreniuk says.

Other CCGs say their flexibility to spend their increased budgets has been limited by national spending commitments on pay, urgent and emergency care tariffs, mental health and primary care. However, due to the relatively large increase in its allocation, Bradford City will still have a good deal of flexibility to shape its spending plans, Ms Lawreniuk says.

Other changes in the funding formula are the introduction of a measure of need for community services; use of the annual average of GP registered lists, ensuring allocations are better able to pick up cyclical patterns in population movement; and improvements in age and gender information.

Blackpool CCG has one of the highest percentage increases for 2019/20 (11.58% in core allocation, leaving the CCG 4.99% under target). A spokesperson for the CCG says a significant proportion of the increase relates to addressing unmet need and the CCG is working through the detail.

‘Workforce remains a challenge in respect of a number of aspects of local capacity. The CCG and ICP [integrated care provider] is already engaged on work to redesign pathways and service delivery models including workforce elements. Commissioning approaches and options to address unmet need and long-term plan requirements are being developed.’

The Blackpool CCG spokesperson adds that mental health need forms a key driver in the CCG’s allocation growth for 2019/20. ‘The CCG has identified the resource to invest in respect of areas included in the Mental health forward view and delivery plans are being developed, but workforce remains a challenge.’

South Worcestershire CCG and Wyre Forest CCG will also receive relatively high uplifts for 2019/20 (8.17% and 8.06%, respectively, in core allocations, leaving both CCGs 4.99% under target). The CCGs, which have a joint management team together with Redditch and Bromsgrove CCG, say the increases give them the opportunity to look at local service provision and what service developments are required. A number of options are being examined in community and mental health services. However, capacity could also be an issue. ‘Local capacity continues to remain challenged, so any service developments will require new ways of working and recruitment of new staff,’ they say.

‘A significant proportion of the CCGs’ uplift will be consumed within the increased tariff prices to acute providers,’ they add.

Some CCGs will have less growth money. Sunderland CCG, for example, will receive a 4.83% uplift in cash terms, leaving it 6.7% above its new target allocation.

David Chandler, the CCG’s chief finance officer, says: ‘Sunderland CCG is pleased to receive our share of the additional allocation growth for the next five years. Coupled with our existing allocation funding, we are confident we can, working with partners, improve the quality of services and health outcomes for our population in a sustainable way and play our part delivering the NHS long-term plan. We expect to be able to meet all our key financial duties including the mental health investment standard and reductions in running costs.’

Big step forward

NHS England’s Mr Style said the new allocation formula had taken ‘a big step forward’ in the estimation of relative need for community services. It has not been included in the formula previously due to lack of data.

The formula for relative need for community health services has been developed using early returns from the community services dataset together with more detailed patient-level data from a handful of local areas.

Mr Style told NHS England board members: ‘This, in particular, reflects higher need for community services in areas with a higher proportion of people aged over 85, particularly in rural and coastal CCGs, but also importantly in some deprived populations in the Midlands and the North. The formula will be refined as data quality improves.’

There have also been improvements to the mental health formula, enabled by better data, particularly through IAPT activity collections. This has resulted in higher need indices for some coastal areas and areas with older populations due to better diagnosis and recording of dementia now coming through in the national data.

As previously trailed, CCGs must continue to bear down on their running costs, with a 20% real terms reduction on their 2017/18 allowances required by 2020/21.

One CCG points to a potential merger and vacancy freezes as a way of delivering most of its running cost savings target, which amounts to more than £2m. While the CCG is keen to see how automation and IT can deliver savings, it feels there is a lack of clarity about what it means. This point is echoed by other CCGs.

Julie Wood of NHS Clinical Commissioners says the reduction in administrative spending will put CCGs under more pressure. ‘Commissioners will still need effective teams and expertise to enact their crucial functions of assuring quality and driving effective integration. It will be critical that these cuts to running costs don’t undermine the efforts happening across the system to transform health and care services for the better.’

As with previous allocations, NHS England has adopted a pace of change policy, moving CCGs to their target allocation gradually. If CCGs received their target allocations immediately it would risk destabilising those over target. At the same time, under-target CCGs may find it hard to get best value from a large overnight increase in their funding.

The policy for the next five years will mean that no CCG will be more than 3.5% below their core target allocation by 2023/24. However, in 2023/24 13 CCGs, mostly in Greater London, are still due to be more than 5% above target.

NHS England chief executive Simon Stevens told fellow board members that no part of the country will be more than 5% below their target allocation in 2019/20.

‘In all honesty, we can say that since the approach to trying to allocate funding based on need began in the national health service in 1976, this will be the fairest and most precise allocation of the growing resources that the NHS has ever seen.’

He added that local areas will have to show in their plans how they will use the funding to narrow health inequalities.

Clearly, the allocations have been made in support of the NHS long-term plan. There is money to protect provider finances and help resolve deficits, but CCGs will be expected to use their additional spending power to commission services that address health inequalities and boost primary, community and mental healthcare, with the ultimate aim of tackling the major causes of deaths.

Rural boost

The new formula appears to direct more funding to rural areas in the long-term, according to Nuffield Trust research director and chief economist John Appleby (pictured).

Professor Appleby and colleagues recently wrote a paper for the National Centre for Rural Health and Care that said rural areas were disadvantaged by the old funding formula.

Professor Appleby and colleagues recently wrote a paper for the National Centre for Rural Health and Care that said rural areas were disadvantaged by the old funding formula.

Subsequently, he has analysed the impact of the revised formula. He says that between 2018/19 and 2023/24, total funding relating to core CCG allocations for predominantly rural areas will increase by 24.2% compared with 22.9% for predominantly urban areas.

This equates to an annual average increase of 4.2% to urban areas compared with 4.4% for rural. He adds: ‘In absolute terms, the 32 predominantly rural CCGs will be getting around £120m more than if there was just an equal uplift.’

The new formula includes an adjustment for unavoidably small hospital provision in remote areas – this is unchanged from the previous formula. Professor Appleby says: ‘It is fair to say that the current adjustment for unavoidable smallness was a first step in trying to address cost pressures in rural areas, focusing, for example, just on acute providers. As such, further work will be needed to calibrate the most appropriate level of funding and coverage of such adjustments.’

He understands that the Advisory Committee on Resource Allocation (ACRA), which recommends changes to the funding formula, will be asked to look again at the adjustments for rurality. The Nuffield Trust report makes a number of recommendations on further work. These include:

- Greater transparency about the nature and scale of mechanisms for compensating for rural costs

- NHS Improvement must be more transparent around the calculations of, and decision-making to approve or reject, local modifications

- ACRA should continue revisiting evidence on costs in consultation with rural trusts, including non-acute providers, and commissioning further research if required

National bodies should also be providing non-financial support to rural commissioners and providers to overcome the challenges they face.

Related content

We are excited to bring you a fun packed Eastern Branch Conference in 2025 over three days.

This event is for those that will benefit from an overview of costing in the NHS or those new to costing and will cover why we cost and the processes.