NHS in numbers: capital and the NHS estate

Old age is the primary reason why the NHS needs to invest in its secondary care estate. The NHS long-term plan acknowledges that ‘some of the estate is old and would not meet the demands of a modern health service even if upgraded’.

Old age is the primary reason why the NHS needs to invest in its secondary care estate. The NHS long-term plan acknowledges that ‘some of the estate is old and would not meet the demands of a modern health service even if upgraded’.

According to NHS Digital’s estates return information collection (ERIC) for 2018, NHS trusts have a total of 9,312 sites, including 233 general acute hospitals, 49 specialist acute hospitals, 103 mixed service hospitals and 658 mental health sites. A further 5,660 sites are classed as ‘non-inpatient’ and there are 2,084 support facilities.

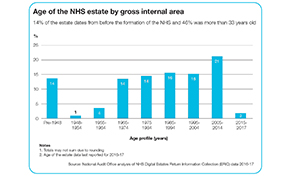

The National Audit Office says that 14% of the estate predates the formation of the NHS and some hospital buildings date back to the Victorian times.

In some cases, facilities need to be improved or maintained, while elsewhere new buildings and equipment are needed.

According to NHS Digital, the backlog maintenance work to restore buildings to an appropriate standard would cost £6.5bn – with £3.4bn of this relating to high or significant risk backlog. High-risk backlog maintenance (£1.1bn) grew by 139% between 2014/15 and 2018/19.

NHS providers’ annual assessment of their need for capital investment was on average £1.1bn higher than their spending limit in the three years up to and including 2018/19.

Despite this, the Department of Health and Social Care transferred £4.3bn from capital to revenue spending between 2014/15 and 2018/19 to help cope with day-to-day financial pressures in the NHS. A further £500m was planned for transfer in 2019/20, before the practice was brought to a halt.

Even though demand for capital outstrips supply, the Department has underspent against its capital departmental expenditure limit (CDEL) by a total of £2.7bn since 2010/11.

The big underspends came in the years before the transfers to the revenue budget became a regular feature. But there have continued to be small underspends subsequently – and a more significant £360m in 2017/18.

These underspends can be a result of delays in capital programmes, meaning funds do not need to be drawn down, some of which could be due to concerns about the revenue consequences of capital spending.

There have been moves to increase the levels of capital available to the health service over the past year. Last summer, there was a flurry of announcements. A £1bn increase in CDEL was provided to support 2019/20 capital spending plans. A further £850m would support the upgrade of 20 hospitals over the coming years. There was also £250m to fund artificial intelligence investment over three years.

A further £200m for diagnostics, delivered over two years, would help to modernise CT, MRI and X-ray equipment. NHS England and NHS Improvement say this will help to address the fact that 14% of CT and 34% of MRI scanners are 10 years old or more.

This was followed up by the unveiling of the Health Infrastructure Plan, which promises to fund 40 hospital building projects over the next decade. Six new large hospitals were awarded £2.7bn in the first wave – although the funds will flow as required over the coming years.

A further 21 schemes – accounting for the remaining 34 hospital projects – were given a share in £100m seed funding to support the development of business cases.

The funding for these various programmes will be needed at different points over the coming years. The long-term capital settlement this summer will be important in setting out future capital spending limits, which will crucially start to clarify how much funding will be available outside these existing commitments for more general capital projects.

The 2020 Budget in March actually set a CDEL of £8.2bn for 2020/21 – an increase of £1.1bn on 2019/20 – although this was before financial commitments were made to support the Covid-19 outbreak. Within this total, just £100m is there to support the HIP, with projects only just beginning. The increase also includes a £683m increase for operational capital investment.

Related content

We are excited to bring you a fun packed Eastern Branch Conference in 2025 over three days.

This event is for those that will benefit from an overview of costing in the NHS or those new to costing and will cover why we cost and the processes.