Covid-19 update: 16 April

Some 4.7 million people in England were waiting to start treatment at the end of February, the highest number recorded since records began in August 2007. Of these, nearly 388,000 had been waiting more than a year. The total waiting figure is 270,000 higher than 12 months ago – a 6% increase. However, the over-a-year waiters represents a 240-fold increase from just over 1,600 a year ago. These long waiters now account for more than 8% of the total waiting list.

Some 153,000 were admitted for treatment in February, a 47% fall on the 286,000 admitted during February a year ago.

Danny Mortimer (pictured below), chief executive of the NHS Confederation, said the performance figures also showed how much the NHS was doing, while still dealing with the Covid-19 pandemic – 1.9 million elective procedures and other care in January and February, alongside treating 140,000 Covid patients. And he said the fact that cancer treatment was in line with February last year was ‘good news’. But he added that the scale of the challenge facing the health service could not be ignored.

‘There is still a major backlog in terms of diagnostic and elective activity as a result of Covid-19, and our own analysis suggests there may be far more below the surface,’ he said.

There was a plan in place to tackle the backlog, he said, and NHS bodies were finding ways to improve throughput and efficiency. The £1bn additional funding from the Budget would help. ‘But health leaders are clear that the NHS will be recovering for years to come, and this must be appropriately resourced in the long term,’ he said. ‘There must also be investment in growing and maintaining the workforce, alongside continued funding to deal with Covid pressures, as we must all be live to the possibility of a resurgence as the national lockdown restrictions continue to ease.’

NHS Providers’ chief executive Chris Hopson pointed out that the last time waiting lists and waits had been so long was in the early 2000s. The solution then had involved five years of more than 7% real terms funding increases. ‘We’re clear in the NHS that we have a responsibility to get through this by doing all we can – by increasing capacity, growing our workforce, finding innovative ways of treating people, and increasing efficiency – but government needs to play its part as well,’ he said.

Productivity impact

Inevitably, with the reduction in non-Covid activity during the pandemic, NHS productivity has reduced. The HFMA Healthcare Costing for Value Institute’s annual costing conference was told that acute sector productivity fell by between 24% and 31% in the first half of 2020/21, with average costs increasing significantly for every point of delivery – non-elective, elective, accident and emergency, outpatient attendances and outpatient procedures.

The figures were gleaned from an Exceptional Quarterly Collection of costs set up last autumn to understand both the costs of Covid care and the impact of the pandemic response on non-Covid activity. The increases in average costs were driven by reductions in activity (meaning fixed and semi-fixed costs are spread across reduced activity) combined with either increases or less-than-proportional decreases in total costs.

The figures helped support the case for the increased funding awarded to the NHS in the spending review, the conference was told.

Right at this moment, the additional pressure from Covid-19 seems to be reducing for NHS trusts. With cases having fallen to under 3,000 per day, daily admissions to hospital continue around the 200 per day mark. And at the start of the week, there were fewer than 2,500 Covid patients in hospital.

However, with social distancing measures having been eased on Monday, there are concerns that virus levels will again start to increase. In particular, more social interaction in shops, bars and restaurants could provide more opportunities for transmission of variants of the virus.

Figures up to 14 April from Public Health England show that there have been 600 genomically confirmed cases of the so-called South African variant and 59 cases of the Brazilian variant – both considered ‘variants of concern’. A variant that was first detected in India, a country currently in the grip of a major coronavirus outbreak, has also been detected in the UK, with 77 cases discovered. Currently labelled a ‘variant under investigation’, there are fears that the ‘double mutant’ variant could be more infectious or less affected by vaccines.

Surge testing is deployed in areas where variants of concern are found. This week, Finchley in north London, Southwark, Lambeth and Wandsworth in south London and parts of Sandwell and Birmingham were all targeted with additional testing and genomic sequencing after cases of the South African variant were found.

Surge testing remains a key tool in enabling the country to continue to move out of lockdown, helping to identify asymptomatic cases before they spread the virus any further. But it is not just about the new variants, testing and contact tracing for the virus in general also have a vital role to play.

The latest report from NHS Test and Trace said that just over 19,000 people tested positive for coronavirus in the week to 7 April – a 34% decrease on the previous week. Some 17,000 cases were transferred to the contact tracing service and 15,000 of these (88%) were reached, with some 12,500 providing details of 62,000 close contacts. Nearly nine out of 10 of these close contacts were reached and asked to self-isolate. The report also shows that results for nearly one in three tests undertaken in the community were received within 24 hours.

In terms of the managed quarantine service for those entering the country, nearly 33,000 people started quarantining at home, with nearly 2,400 in a managed quarantine hotel.

In Scotland, in the week to 11 April, 3,600 unique contacts were traced from 1,700 cases recorded in the contact tracing software.

Defence model

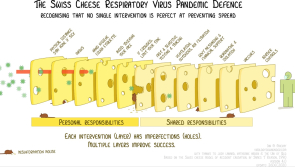

Testing and isolation along with personal responsibilities such as handwashing, mask wearing and maintaining social distance have been likened by Australian virologist Ian Mackay to slices of swiss cheese in an infographic that went viral over the end of last year. The idea behind this model for pandemic defence is that no single intervention is perfect, each layer has its failings or holes. But having lots of layers provides the best chance of preventing transmission.

Vaccines are seen as one of the key slices in the world’s defences against Covid-19. In the UK, the programme continued to make good progress. The government announced this week that it had hit its phase 1 vaccination target a few days early – offering jabs to everyone over 50, health and care workers and the clinically vulnerable. This group accounts for 99% of Covid deaths during the pandemic. Phase 2 has now begun with the programme moving on to the under 50s.

This is in line with the final advice from the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI), updated this week. While the committee did consider the option of vaccination based on occupational groups at higher risk of exposure, such as teachers, it has again said that the programme should continue to vaccinate on the basis of oldest first.

The Department of Health and Social Care said that around 95% of people aged 50 and over had received a first dose of vaccine, while 92% of people who are clinically extremely vulnerable had also received their shot. In Scotland virtually all over 60-year-olds have now received a first dose, 96% of 55-59-year-olds and 84% of 50-54-year-olds – in total this amounts to 60% of the whole adult population.

In Wales, 52% of the whole population have had a first dose with 18% being fully vaccinated. Figures from Public Health Wales show that more than 50% of 40-49-year-olds have also been given a first jab, including those who qualified for an earlier vaccination because of being clinically vulnerable or because of their status as care workers. Counting individuals once only in their highest priority group, just over 30% of 40-49-year-olds have already been vaccinated. Northern Ireland has passed the 1 million vaccination mark, with 844,000 first doses and nearly 240,000 seconds doses.

England followed Wales and Scotland in rolling out the Moderna vaccine this week – making it the third vaccine available for use alongside those from Oxford/AstraZeneca and Pfizer/BioNTech. However, the fall-out from concerns about very rare cases of blood clotting, potentially relating to the AstraZeneca vaccine continued. There have been assurances from the European Medicines Agency and the UK Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency that the benefits of the vaccine still far outweigh any risks. And the UK has adopted a precautionary approach of offering under 30-year-olds an alternative vaccine, as the risk benefit was ‘relatively finely balanced’ for this group at low levels of virus prevalence.

However, Denmark this week suspended use of the vaccine. While some countries have limited its use, Denmark is the first country to actually drop AstraZeneca from its immunisation programme. Concerns over blood clotting have also broadened to a vaccine produced by Johnson and Johnson (Janssen) after six cases were found in the United States, all involving women following vaccination. A joint statement from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drugs Administration said the bodies were recommending a pause in use of the vaccine ‘out of an abundance of caution’.

Nearly 7 million doses of the vaccine, which is based on a similar technology to the AstraZeneca vaccine, have been administered in the US. The company put out a statement saying it would proactively delay the rollout of the vaccine in Europe and pause all clinical trials.

Blood clots study

Meanwhile, study by researchers at the University of Oxford this week reported that the risk of the rare blood clotting known as cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) was higher following Covid-19 infection than it was following vaccination. The study counted the number of CVT cases diagnosed in the two weeks following diagnosis of Covid-19 or after the first dose of a vaccine – considering the different vaccines separately. It also compared these to incidences of CVT following influenza and the background level in the general population.

It found that CVT is more common after Covid-19 than in any of the comparison groups, with 30% of these cases occurring in the under 30s. The risk was between 8-10 times higher than post vaccine and about 100 times higher when compared to the baseline in the general population. In 500,000 Covid patients, CVT occurred 39 times in a million. In 480,000 people receiving the Pfizer or Moderna vaccine, CVT occurred in four in a million, while CVT has been reported to occur in about five in a million people after a first dose of the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine.

With continuing debate about the need for vaccine certification to enable greater social mixing and travel, the government launched a five-week consultation on whether staff working in care homes for older adults should be required to have a Covid-19 vaccine. The government’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (Sage) recommends that 80% of staff and 90% of residents need to be vaccinated to provide a minimum level of protection against Covid outbreaks. Only 53% of older adult homes in England are currently meeting this standard, with staff vaccination rates below 80% in more than half of local authority areas and all 32 London boroughs.

Health and social care secretary Matt Hancock (pictured) said that many care homes had called for vaccines to be a condition of deployment. ‘The vaccine is already preventing deaths and is our route out of this pandemic,’ he said. ‘We have a duty of care to those most vulnerable to Covid-19, so it is right we consider all options to keep people safe.’

As the week closed, Scotland brought forward the easing of existing restrictions. As of Friday, six people from six households can now meet outdoors – in line with permissions in England. Travel within Scotland is also now allowed for outdoor socialising, recreation and exercise. Northern Ireland also announced further easing of restrictions from 23 April. The success of the vaccination programme and current low case levels are a cited as major reasons for enabling these steps. All eyes will now be on how this greater freedom impacts on case levels and hospitalisations.

Related content

We are excited to bring you a fun packed Eastern Branch Conference in 2025 over three days.

This event is for those that will benefit from an overview of costing in the NHS or those new to costing and will cover why we cost and the processes.