Up and running

The push to produce more robust and detailed costing data across the whole of the English NHS has reached an important tipping point, according to NHS Improvement costing programme director Colin Dingwall. However, there is still significant work ahead, with the next year being particularly critical.

Three years ago this month NHS Improvement – or Monitor, as it was then – set out its proposals for a new approach to costing. Its Costing Transformation Programme (CTP) would see the whole service costing activity down to the patient level, with a single submission of data replacing three pre-existing collections (reference costs, education and training costs and a voluntary patient-level cost submission).

Crucially the new approach would require organisations to adhere to new common costing standards – earlier adopters of patient-level costing had used logical but varied approaches. Adhering to detailed new standards would not only support local decision-making, but would open the door to more straightforward bench-marking across providers and better inform national price-setting.

Since then, there have been two versions of new costing standards for acute providers, draft versions for mental health and ambulance service providers – with only community services yet to see their own dedicated costing guidance (this is due to follow early in 2018). And while this requires more of costing teams, we are also seeing the first steps towards the promised single collection.

Next year will see the first combined collection for reference costs and patient-level costs. And in November NHS Improvement consulted on proposals to mandate the collection and submission of patient-level cost data using the standards from the year after (covering financial year 2018/19 onwards). This is an essential step towards enabling the regulator to switch off reference costs at some point downstream – submission of which is currently a licence condition for providers.

So there has been huge ground covered, but for Mr Dingwall the tipping point is the fact that this year over 60 acute trusts submitted cost data to NHS Improvement using the new standards – representing about £20bn of NHS spending. In addition, so far, 28 trusts have subsequently been given access to a new portal, enabling them to analyse their own data and compare it with all participating providers or a chosen set of peers. Other trusts will get access to their data in the coming weeks.

Delivering value

Robust costing data is not an end in itself – it is using the data to identify and drive improvement that delivers the real value. So enabling providers to start this analysis and comparison through the portal is a key milestone.

‘We are starting to get traction,’ says Mr Dingwall, who has worked on the CTP since 2015 and has just been appointed to the director role. ‘We’ve spent two to three years piloting and rolling out the standards and we’ve now got real data to work with. It feels like a tipping point.’

The data has got a lot of people quite excited. ‘I’ve really detected a shift in how much importance is attached to costing among costing teams, clinicians and colleagues across the NHS,’ adds Mr Dingwall. Reference costs continue to be of value, but there are limitations – too much averaging and an inability to drill down into the averages to see what is driving costs.

Patient-level costs is a potential game changer – still enabling comparison at specialty or HRG level, but also allowing organisations to drill down to see how individual patient costs have contributed to this average. Or they can look at components of overall costs – theatres or pathology, for example – again, at an aggregated or individual patient level. This will help identify and understand variation.

NHS Improvement’s teams looking at operational productivity, the Model Hospital and Getting it right first time, as well as NHS England’s RightCare programme, have all shown a real interest in the more detailed cost data, says Mr Dingwall. They all recognise the huge potential in being able to look at variation in outcomes and pathways and link this to firm patient costs – within individual organisations at first and across whole pathways in time.

Mr Dingwall describes the current position as ‘a huge achievement’, recognising that it is very much down to the efforts of costing teams and patient-level information and costing system (PLICS) suppliers. However, he stresses that there is still a long way to go. ‘Next year will be critical,’ he says.

Rolling out

The 60 or so trusts that submitted costs covering the 2016/17 financial year represent the majority of the 78 trusts that had indicated they wanted to take part. They also make up 40% of all acute trusts. Having proved the submission process works at scale, next year the plan is to add as many as possible of the rest of the acutes, along with early implementers from other sectors.

The point is to get organisations used to the process – collecting, submitting and resubmitting after having data quality issues highlighted. ‘Getting clinical engagement and the quality of the data up will be a challenge that will be with us for the next few years,’ says Mr Dingwall. ‘But I feel like the building blocks will be in place and we can start doing some really good work.’

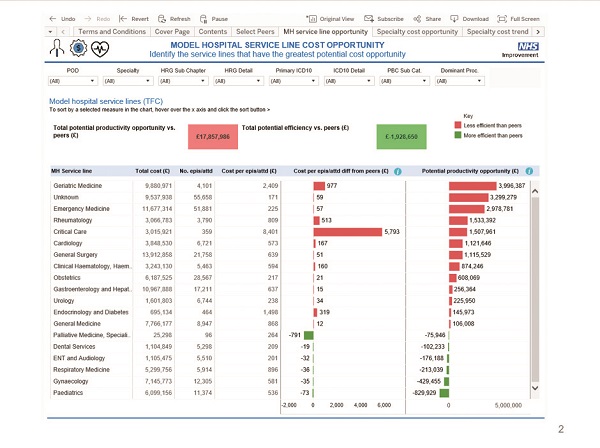

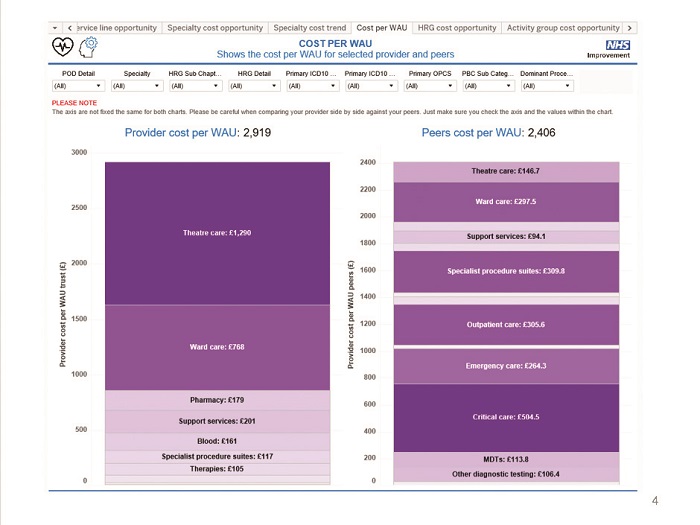

NHS Improvement opened its PLICS portal in October, with 28 trusts being given access to their activity and cost data to help them identify productivity opportunities. ‘It’s a chance to see where your costs are divergent from your [self-selected] peer group,’ says Mr Dingwall. ‘And it encourages you to dive in and see why you are different.’

Users can look at costs by service line, HRG or specialty, and they can see their cost per weighted activity unit (WAU) – the weighted activity unit introduced by the Carter review. They can look at this at the component level – for example, pharmacy or radiology costs per WAU – and in due course they can see trends over time.

On their own data, users can drill down to the patient level for different procedures and treatments. And a new data quality tool will also help organisations with the quality of their submissions – highlighting where trust data lies outside the typical range and potential data issues to investigate.

Organisations are still getting used to the new approach laid out in the standards and not all organisations have the feeds in place to supply the required information to allocate all costs accurately across patients.

‘There are of course some data quality issues – but this is a shared challenge and we’d rather push the data out and work with trusts on those issues, because they know what’s going on in their trusts’, says Mr Dingwall. ‘In fact, if we don’t take on the data quality challenge, we will never get the cycle of improvement.’

He says trusts have to embark on a ‘long iterative path’ to improve quality, but that clinical challenge is a core part of the process.

This year, patient-level cost submitters were given additional time to submit reference costs. Next year, the parallel collection of reconciled sets of both costs will be a challenge to costing teams.

But if the submissions reconcile and the new system is shown to work, NHS Improvement says, ‘from 2019 we expect there to be a single national cost collection for acute services’. These costs would then replace reference costs in informing the tariff.

Avoiding this year’s late release of the reference costs grouper should help reduce some stress, but there is another measure that aims to reduce the burden of collection. The integrated education and training reference costs submission will not be required next year. Instead reference costs will be submitted net of education and training income.

This is a one-year only measure and only relaxes the requirement to submit data. ‘Education and training needs to be costed every year,’ says Mr Dingwall. ‘If you are spending any significant amount of money, you should be able to monitor and manage your costs.’ As well as reducing the burden on costing teams, this will enable the education and training costing process and tariffs to be refined (see box).

Acute trusts face the earliest deadline for switching to patient-level costing. During October and November, NHS Improvement consulted on making it mandatory for acute trusts to report patient-level costs in line with the standards from 2019 (covering the 2018/19 financial year). Mr Dingwall is confident this can be achieved.

Some 84% of acute trusts have implemented a PLICS system. A further 10% are mid-implementation and the rest are planning implementation. But again, he encourages all trusts to take advantage of learning from next year’s voluntary submission. He says suppliers are more experienced this year to support new submitters and a further package of support is being planned by NHS Improvement for both first-time and repeat submitters.

He also insists the focus is not solely on acute providers. Ambulance services have taken the programme ‘very seriously’, with four pilot trusts submitting data this year and he hopes that more trusts will get involved next year. Mr Dingwall believes the data from this part of the exercise will be a critical step forward towards gaining a better appreciation of the whole patient pathway. There has been good progress too with mental health and community service providers, he says – a mental health pilot collection was under way during November. However, the sheer volume of work being undertaken and the need to support different collections next year means that NHS Improvement is now planning to phase some of its outputs over the next year.

Changed timetable

So January will see publication of the third version of acute and second version of ambulance standards, along with transitional education and training standards for use in 2018. Then there will be a second publication in March of mental health (version 2), community (version 1) and draft education and training standards, setting out the PLICS-based approach to costing training activities.

Although the phasing is a reflection of the workload at the centre, Mr Dingwall also says it is important that NHS Improvement is able to give ‘very specific attention to each sector’ rather than publishing everything at the same time and then being spread too thin to support everyone.

He is full of praise for the costing community. It is supportive of the programme, willing to engage and demanding of information. But there have been suggestions that finance directors have yet to fully engage with the costing agenda. Mr Dingwall admits the programme has focused more on working with costing teams and has had ‘less opportunity’ to engage with directors so far. But they are vital to the success of the programme as they, along with their board colleagues, are key to properly resourcing the initiative and then changing organisational processes so that costing data is used routinely to drive improvement and inform decision making.

However, he suggests that they instinctively understand they should be doing this – underlined by the fact that every acute provider has made a business case for PLICS. He points out that there has also been a good response so far to the invitations to submit data voluntarily.

‘Our attention has been on getting the technical building blocks in place,’ says Mr Dingwall. ‘Our focus will shift in the coming months to concentrate more on finance directors than we have so far.’

He is clear that patient-level costing has to be about more than submitting better quality data – it has to be used in local health systems. ‘If this becomes about compliance, we will have the same problems that we have had with reference costs,’ he says.

However, he believes there is genuine enthusiasm for the data, not just among the various initiative leads (such as GIRFT and the Model Hospital), about how costing can lead to better outcomes. For example, the NHS Improvement team is already engaging with the nine pilot accountable care systems. ‘It feels like we are pushing at an open door and there is a lot of demand there.’

Mr Dingwall argues that the case is compelling and finance directors understand this. The consultation on mandating collection for acute activity suggests a mandated approach would cost no more than the current ‘business as usual’ (mandatory reference costs and voluntary patient-level costs slowly

getting dropped over time). The average annual cost of this steady state for a trust is estimated to be £225,000 a year, compared with £222,000 for the patient-level approach.

While the impact assessment makes no attempt to quantify the service-wide financial benefits of mandated patient-level costs, it offers a range of examples where recurrent benefits far outstrip costs. ‘Each example we’ve found shows that the costs of using patient-level costs are typically recouped by just one use of the data,’ says Mr Dingwall. ‘The business case is fairly self-evident.’

There are plans to work with NHS Digital and NHS England on bringing cost data together with outcome data. And new costing regional forums, being run in conjunction with the HFMA, aim to build knowledge, capability and confidence on how to use cost data to deliver value. These discussions aim to involve non-costing practitioners too, including clinicians, informatics and transformation managers.

Mr Dingwall insists he is not downplaying the challenges that still lie ahead. He recognises that the current financial position means that time – to improve costing and to start using patient-level cost data in discussions with clinical teams – is limited. But the service has turned a real corner with this year’s release of data back to the service.

The quicker organisations start to mainstream use of robust cost data, the sooner it can start to help ease financial pressures. ‘Yes, there is an overhead to patient-level costing, but the benefit coming out is potentially very significant,’ he says.

The price of education

Education and training tariffs were introduced in 2013 to remunerate providers for the costs they incur delivering medical and non-medical training. However, these interim

tariffs were relatively blunt – effectively one rate for each placement type: non-medical; undergraduate medical; and postgraduate medical – all based on a placement fee with the postgraduate medical tariff also including some salary support.

Since then, trusts have been required to submit cost data based on revised guidance covering their training activities. This has served two purposes – to improve costing information for both training and service costs and to help develop training tariffs that

more accurately match the costs of delivering training.

Data from the first three years of training cost collection have been used to design a new currency – known as education resource groups – and this will be subject to a stakeholder engagement exercise in 2018.

Under the new proposals for non-salaried training (undergraduate and non-medical), there is likely to be a single currency for each profession – for example, adult nurses, mental health nurses, pharmacy technicians and radiographers.

For the salaried postgraduate medical placements, groups would be focused on the foundation years, core training and higher specialty training – with tariff split by specialty. This reflects the fact that the cost phasing can be different in different specialties – neurosurgery requiring more consultant support in the late stages of training, for example.

The postgraduate tariffs are likely to be in a similar ‘placement fee plus variable element’ format, linked to salary levels, although not a direct percentage.

Jennifer Field (pictured), head of finance strategy at Health Education England – the body tasked with developing the new currency – says any proposed changes to tariffs will need a full impact assessment and there would potentially need to be some transition.

‘But there would not be the same big gains and losses that accompanied the introduction of the interim tariffs in 2013,’ she says. The cost data collected to date suggests that, overall, NHS providers are paid less for training than it costs, indicating some cross-subsidisation between service and training. This is not across all activities, however. ‘The tariff for medical placements is higher than the costs, but the payment for non-medical is lower than trusts say it costs,’ she says.

This may not change funding overall for a trust – as most will provide both medical and non-medical training. But a more detailed currency and robust costs would enable prices to be set to cover specific costs, enable funding to flex with training activity changes and allow the Department to incentivise increases in activity where appropriate.

There will be no education and training cost collection next year (covering 2017/18), although trusts are encouraged to keep costing activities locally. Guidance for netting off training income (for 2017/18) will be released in January with new costing standards – putting training costing guidance into the NHS Improvement format – in March.

The sector’s feedback to the proposed currency will be reviewed, although April 2019 is the first time the new currency could be introduced.

Related content

We are excited to bring you a fun packed Eastern Branch Conference in 2025 over three days.

This event is for those that will benefit from an overview of costing in the NHS or those new to costing and will cover why we cost and the processes.