Prescribing: medicinal value

Prescribing budgets are a key concern for clinical commissioning groups. It is hard to ignore a budget that makes up around 10% of overall spending. The focus on increasing levels of lower cost generic prescribing has shifted in recent years – with this particular battle largely won. But the need to counter inflationary pressures on drug bills remains – especially in such a difficult financial environment – and there is a belief that CCGs can improve the value delivered by their spend on medicine.

Perhaps one of the most eye-catching promises in the long-term plan was to increase primary care staff by 20,000 by 2023/24. These staff will work in new primary care networks across local general practices and clinical pharmacists will be one of the first two of five primary care roles to be funded (along with social prescribing link workers, physician associates, physiotherapists and community paramedics).

By 2023/24, a typical network of 50,000 patients could have its own team of six whole-time equivalent pharmacists in place. On the face of it, the move is about taking pressure off GPs. In 2015, the government committed to increasing the number of doctors working in general practice by 5,000 by 2020. Although training places have increased, it seems unlikely that this target will be achieved. And in May, the Nuffield Trust highlighted that the number of GPs has recently seen a sustained fall relative to the size of population.

Patient-facing roles

The new scheme to boost the wider primary care team is an attempt to meet growing patient demand in a different way. Pharmacists will take on some direct patient-facing roles. Job descriptions in January’s new GP contract framework to support the long-term plan make it clear that these new clinical pharmacists will be prescribers – or train to become prescribers – and will take responsibility for the care management of patients with chronic diseases.

But it is not just a workforce fix. These pharmacists will undertake structured medication reviews, in particular focusing on the elderly, people in care homes, those with multiple long-term conditions such as COPD and asthma, and people with learning disabilities or autism. They should also take a lead role in ensuring antibiotic prescribing is in line with guidance.

NHS England’s chief pharmaceutical officer, Keith Ridge, believes too many patients are prescribed medicines that they either may no longer require or which might need adjusting and the new pharmacy teams will help address this. ‘Rather than assuming there’s a pill for every ill, increasing the availability of specialist health advice in care homes will mean residents get more personalised treatment, reduced chances of being admitted to hospital and people will have a better quality of life, for longer,’ he says.

This initiative is in fact a key component of a broader push on medicines optimisation. A medicines value programme led by NHS England was launched as a follow-up to the Next steps on the NHS five-year forward view and the Carter report on acute hospital productivity. While medicines are a key component in many people’s treatments, there are a number of issues that suggest room for improvement.

For a start, around 5% to 8% of hospital admissions are medicines-related and many of these are preventable. In 2017, NICE calculated that potentially avoidable adverse drug reaction-related non-elective admissions were costing the NHS some £529m based on 2012/13 costs. And a more recent research paper has suggested that definitely avoidable adverse drug reactions are costing the NHS nearly £100m a year.

It is estimated that up to 50% of patients don’t take their medicines as intended, which could have an impact on their health. But some estimates suggest that waste of drugs in primary care costs the NHS £300m a year. Overuse of antibiotics is leading to bacteria becoming resistant to them. And polypharmacy is an increasing concern, with some figures suggesting that more than one million people – often the elderly – now take eight or more medicines a day.

The medicines value programme has four strands covering: a framework for access to and pricing of medicines; the commercial arrangements that influence price; developing the infrastructure to support the supply chain; and optimising the use of medicines.

It is in this latter area where commissioners – supported in some initiatives by regional medicines optimisation committees – can play their own part in optimising use of medicines locally.

According to the latest report from NHS Digital, drug costs are evenly split between hospitals and the community. After significant spending increases for hospital medicines in recent years, primary care prescribing now accounts for just under 50% of the total £18.2bn cost of medicines in the NHS in England.

Primary care prescribing costs have increased by just 2.6% between 2010/11 and 2017/18, falling by 1% in that final year. However, while there are much bigger increases in hospital drug costs – driven by many of the new drugs for cancer and other areas – prescribing remains a key issue for CCGs. Spending can be volatile and subject to pressures outside of CCGs’ control – some £350m of CCG overspend on overall budgets related to exceptional levels of concessionary prices for generic drugs in 2017/18, for example.

So, keeping an eye on costs remains a major focus. Carol Roberts, chief executive of PrescQIPP – a not-for-profit NHS-funded organisation that produces evidence-based resources for CCGs to improve medicines-based care – says there continues to be huge pressure on CCGs to reduce or contain prescribing costs year-on-year. ‘It is getting a lot harder to look for savings,’ she says, ‘all the easier stuff has been done.’

Reducing the use of medicines with low or no clinical value has been a fruitful area for many commissioners. In partnership with NHS Clinical Commissioners, NHS England published initial guidance in 2017 on 18 medicines that should no longer be routinely prescribed in primary care, which could lead to savings of up to £141m across England.

This was followed in March last year with guidance on 35 conditions where over-the-counter medicines could be used instead of being prescribed, saving the NHS a further potential £100m. A third wave of nine items has recently been consulted on and guidance issued limiting gluten-free products on prescription to bread and/or gluten-free mixes.

Sunderland Clinical Commissioning Group acknowledges that value-based prescribing has helped reduce spending over the last year and improved both safety and quality. It allocates around 10% of its programme budget to prescribing, and in 2018/19 reported a 7.5% reduction in prescribing spending compared with the previous year.

‘On a national level, we also saw reductions resulting from “no cheaper stock obtainable” (NCSO) prices agreed centrally, which last year had caused a pressure of around £140,000 per month and this year reduced significantly,’ says CCG chief finance officer and deputy chief officer David Chandler. But a new mechanism around repeat prescribing also made a significant contribution.

‘Our in-house medicines optimisation (MO) team has led the implementation of a repeat prescribing ordering scheme with practices, which has reduced waste in the system by cutting the number and value of drugs being inappropriately dispensed,’ says Mr Chandler. ‘Based on similar schemes in Luton, Coventry and Rugby, South Sefton and Southport CCGs, we believe this will save around £1.5m recurrently, which we will be able to reinvest into other frontline services.’

The scheme ends the practice of pharmacies automatically issuing repeat prescriptions and puts the patient back in the loop – leading to a noticeable change in prescribing activity.

The CCG also operates a gain share scheme with practices and has established a system-wide medicines efficiency group, including the local acute trust and neighbouring CCG, to enable a more integrated approach to medicines optimisation.

CCG head of medicines optimisation Ewan Maule echoes PrescQipp’s Ms Roberts, stressing that simple improvements (such as increasing generic prescribing) are no longer available. ‘Now we are tackling more entrenched prescribing issues that are systemic and take more unpicking,’ he says.

For Sunderland, this includes looking at the issues around the prescribing – and potential over-prescribing – of analgesics and opiates in particular. Many areas are looking to tackle this (see box).

In other prescribing areas, CCGs will have different challenges and opportunities to improve the value from their use of medicines. There are significant resources to support CCGs looking at variation in prescribing activity (see box, page 12) – far more than for hospital care. The hope is that with the existing pharmacy teams in CCGs, combined with new cohorts of clinical pharmacists in general practice, the NHS can make further inroads into this variation where it is unwarranted.Getting behind the variation

There is a significant amount of primary care prescribing data to support CCGs with medicines optimisation and the delivery of cost improvements.

The source data comes from NHS Prescription Services at the NHS Business Services Authority, which processes around one billion prescription items for pharmacists each year. It makes this prescription data available via its ePACT2 online system, with data online six weeks after the dispensing month. It provides analysis, reports and dashboards.

There are also other complementary ways to interrogate this rich source of data. Openprescribing.net – built by EBM DataLab at the University of Oxford – enables the BSA raw prescribing data to be examined by CCG or general practice.

For example, CCGs can look at their relative performance across more than 70 standard measures, such as the high-cost proton-pump inhibitors as a percentage of all PPIs, or their prescribing of low-value items. It also highlights the biggest cost saving opportunities for each CCG each month.

PrescQIPP started in 2010 as a programme run by the East of England Strategic Health Authority and is now a UK-wide not-for-profit community interest company funded largely by subscriptions from CCGs, commissioning support units and health boards.

It produces evidence-based bulletins and analysis (see chart, right) on therapeutic areas and enables users to drill down to practice level for all its scorecards. It also provides skills training and e-learning.

NHS RightCare provides a range of data for CCGs based on different programmes of care. Where-to-look data packs identify where the biggest opportunities exist for improvement both in terms of outcomes and spend.

As part of this analysis, the packs provide data on primary care prescribing in the different programme areas (such as cancer, respiratory and musculoskeletal), comparing each CCG with 10 similar CCGs and the ‘best’ five of these CCGs.

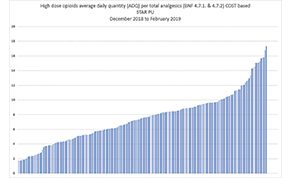

Figure 1 (PrescQIPP data): High-dose opioids average daily quantity per total analgesics (BNF 4.7.1. & 4.7.2) COST based STAR PU, December 2018 to February 2019

Tackling opioid dependency

The use of opioid painkillers has dramatically increased in the UK over the past 20 years, rising by a third between 1998 and 2016, according to the National Institute for Health Research. Yet there is growing concern about the risks for patients, especially given there is little evidence that these drugs are helpful for long-term pain.

Many CCGs are now looking at this area of prescribing practice, in part driven by the inclusion of immediate release fentanyl on NHS England’s list of 18 items that should not routinely be prescribed.

Mid Essex Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) has been looking at this area for a number of years, but chief pharmacist Paula Wilkinson (pictured) says that the national programme helped the work to gain traction.

number of years, but chief pharmacist Paula Wilkinson (pictured) says that the national programme helped the work to gain traction.

Typically, the number of patients taking opioid medication above a safety threshold of 120mg/day can be small – but the costs can be significant. At the start of the programme, the CCG was spending around £500,000 annually on immediate release fentanyl. This has now reduced to around £300,000 across just 13 patients.

Ms Wilkinson stresses that the improvement has needed a comprehensive package of support and is a journey. ‘This has to be done in partnership with patients,’ she says. ‘It takes time and you need to help them to reduce dependency on the product gradually, perhaps moving onto a morphine equivalent dose as a first step.’

The CCG publishes all its prescribing policy statements online and has produced an opioid resource pack to support GPs in ending all new prescribing (other than in connection with hospice care) and reducing prescribing and developing treatment plans for existing patients. The work around fentanyl is part of a wider programme to reduce prescribing and dependence on all high-dose opioids across the CCG (involving some 650 patients).

Recognising the time needed by GPs to spend time discussing this with patients, the CCG has been exploring setting up a dedicated service to which GPs could refer dependent patients. It is now hoping to take this forward as part of support provided through the new primary care networks.

‘We are looking to see how we could use some of the funding to support GPs through PCNs to engage with pharmacists or funding additional time for existing pharmacists working in general practice,’ says Ms Wilkinson.

It has also been redrafting its pain pathway, looking to move patients onto non-pharmacological treatments – such as cognitive behavioural therapy and improved exercise – once the acute phase of treatment is over.

Once the new service is operational later this year, Ms Wilkinson says the CCG could have supported all its patients off immediate release fentanyl within 18 months.

This would release further significant resources, which will help support further and more appropriate services for patients living with chronic pain.

Related content

We are excited to bring you a fun packed Eastern Branch Conference in 2025 over three days.

This event is for those that will benefit from an overview of costing in the NHS or those new to costing and will cover why we cost and the processes.