Feature / Leading by example

The NHS has long been condemned as being data rich, but information poor. And managers have frequently complained about the time-consuming returns they submit without the contained data being put to any apparent useful purpose. The new Model Hospital published by NHS Improvement is trying address both these complaints.

Actually ‘new’ isn’t quite right. Born out of a recommendation from the Carter report on productivity in acute providers, the Model Hospital has in fact been up and running in prototype format since March 2016. However, April sees it ‘launched’, albeit without fanfare, in its first iteration – making good on a specific Carter-set deadline.

Lord Carter’s idea was to help NHS providers – acute providers in the first instance – improve productivity across all their frontline and back-office services by identifying ‘what good looks like’.

More specifically, the Model Hospital project would show how different hospitals performed across a series of service and function specific metrics – helping organisations to compare their productivity, quality and responsiveness with their peers, identify best practice and find opportunities to improve value.

There are already examples of such portals around the globe – a cost and activity information system in the Australian state of New South Wales is well regarded (see Healthcare Finance July/August 2016, page 23). And the English system would in some ways be even more ambitious, eventually covering all service lines and based on comprehensive patient-level costings.

There are longer term plans – again to comply with Carter recommendations – for the Model Hospital to be used as the basis for an integrated performance framework. But Emmi Poteliakhoff, NHS Improvement’s director of Model Hospital and analytics, says the focus of the Model Hospital is to support hospitals, not judge them.

‘The Model Hospital is about presenting data and information to people to aid understanding and enable them to compare against other organisations for their own learning,’ she says. ‘It is about improvement rather than stick waving.’

She insists the model is not about ‘naming and shaming’, but there are no apologies for building the new Model Hospital on a foundation of almost complete transparency. Although the public won’t be able to see the Model Hospital data in this development phase, anyone working in NHS providers can be given access – with non-executive directors a particular target group. Trusts will be readily identifiable and their relative performance clearly visible in graphical displays. The system also uses red and green colours so that trusts can quickly see which quartile their performance puts them in.

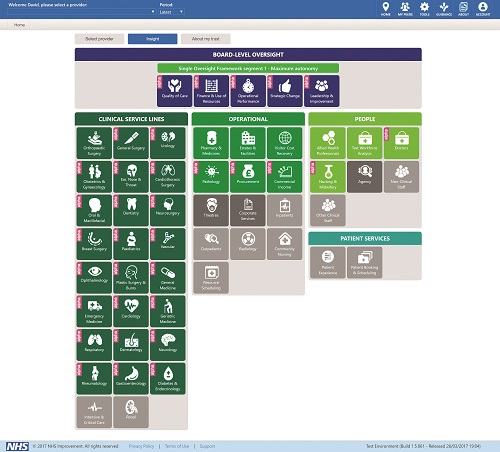

On accessing the portal, there are five main ways into the Model Hospital. A board-level oversight ‘lens’ is structured to align with the single oversight framework, with compartments’ for:

* Quality of care

* Finance and use of resources

* Operational performance

* Strategic change

* Leadership and improvement

Compartments of more detailed metrics are then viewed through four further lenses covering: clinical service lines; operational activities; people; and patient services. It is a rapidly expanding database. The compartments initially released as part of the prototype have already been supplemented and there are plans for major expansion of the clinical service lines covered, in particular to support the expanding coverage of the Getting it right first time initiative.

In the April release, the Model Hospital has 34 compartments live (in addition to the board level dashboard) including almost 2,000 metrics.

The Carter report identified staff costs (£34bn for acute trusts) as ‘the biggest opportunity’ for productivity and efficiency savings – contributing about £3bn (with medicines and diagnostics) to Carter’s overall £5bn savings target. To support this, a workforce analysis compartment provides detailed analysis of clinical activity per staff member broken down by various disciplines within different specialties. More detail again can be found within dedicated ‘people’ compartments looking at doctors, nurses and allied health professionals.

To ensure everyone is using a common currency when talking about hospital output, the Model Hospital makes extensive use of the weighted activity unit (WAU) – this provides a way of taking complexity and casemix into account when talking about the clinical activity of different hospitals. The WAU has been well trailed – by Carter (alongside the related adjusted treatment cost) and subsequently (see Healthcare Finance, March 2016). But there are hopes that it can become the established way of comparing productivity (for example, the cost per WAU, staff numbers per WAU, or spend on high cost medicines per WAU).

Soon after the Carter report was published, there was criticism that the new high-level ‘cost per WAU’ productivity metric, which ranges from £3,000 to £4,100 across all acute trusts, was undermined by its reliance on flawed reference cost data. Reference costs submissions for 2014/15 were found to be materially inaccurate for half of a sample of audited trusts.

Ms Poteliakhoff (right) says there is ‘a

good awareness of the weaknesses of reference cost data’. Not all trusts currently prioritise the cost data and while data has improved in recent years, it has not improved fast enough. This recognition of the problems with reference costs – coupled with an appreciation of the potential value of granular, robust patient-level costs – is inspiration for NHS Improvement’s ongoing Costing Transformation Programme.

That programme is ambitious in supporting the whole English service to start costing at the patient level using a new, consistent and mandatory methodology.

‘Once that is in place, it will revolutionise the work we are doing on the Model Hospital,’ says Ms Poteliakhoff. ‘It will give us a more accurate picture of operational intelligence that providers need to make decisions.’

She points out that new patient-level information and costing systems are as much about the patient-level information – what tests, drugs or therapies a patient has received – as they are about the costs.

The Model Hospital’s value may be enhanced with a more detailed costing foundation, but Ms Poteliakhoff says there is huge value already in the system and that data is good enough to help trusts ask questions and highlight where trusts are outliers in terms of productivity.

Data quality has long been a problem for the NHS in moving towards more evidence-based decision-making. It has often been too easy to ignore or dismiss variation on the basis of not believing the data. But there is also a recognition at NHS Improvement that the way to improve data is to use it and make it visible. So NHS Improvement is playing a short and long game with the Model Hospital. There is immediate value from the outset (see box below) and some compartments that are already proving their worth among users – the pharmacy and medicines, nursing and midwifery and orthopaedic surgery compartments, for example, have all been accessed more than 1,200 times since the start of the year. But the value of the resource will grow as data improves.

A lot of the finance data is taken from audited accounts and so is understandably viewed as robust. These figures need to be adjusted to reflect the fact that the total expenditure reported in the accounts is different from the quantum included in reference costs.

The electronic staff record is also widely used by the Model Hospital as a data source. This is primarily a payroll system, not a data collection system. And while it is extremely reliable at the aggregate level, coding at a more detailed level can be less consistent. So, while a trust might accurately have its nurse numbers and bandings accurately recorded for the organisation as a whole, it may not have these nurses accurately assigned to different service lines. ‘By allowing trusts to see the data and make use of it for benchmarking and learning, it will provide an impetus to standardise the way they code,’ says Ms Poteliakhoff.

Similarly NHS Improvement hopes the greater visibility of data will encourage providers to review the quality and completeness or other returns – to joint registries for example.

Most of the data in the system is already produced or submitted by trusts as part of regular returns. However, the Model Hospital plays this back to trusts alongside how other trusts – or a self-selected peer group – are performing.

So a trust may have suspected that its skill mix among speech and language therapists was too high or too low, but it would not have had comparative data to back this up or challenge existing performance.

Some metrics have required new data collections. This has been the case for both pathology (collecting data about the costs of different types of test) and corporate services (using a more sophisticated cost analysis than the pay-only estimates used in the Carter report). This approach will be used where necessary so that useful metrics are included, but also recognising that the service cannot support a major increase in data collections.

A number of clinical service compartments and corporate services should come on line from mid-April. Compartments aligning with the new GIRFT specialties will include subsets of the metrics identified for detailed use by the programme.

Growing interest

Even while still in its prototype stage the Model Hospital has developed a reasonable audience with some 3,350 registered users and more than 10,000 page ‘hits’ a week. Within this NHS Improvement has identified more than 120 ‘power users’ who have returned to the tool at least 25 times – with the top 10 users logging in on average 160 times each. More than a quarter of active users have logged in at least 10 times.

So there is justification for saying users are doing more than satisfying their curiosity. Activity to date suggests that senior finance professionals are prominent in this user group.

The Model Hospital is an ambitious project. Few people argue against the theory of sharing robust data on wide-ranging activities to support decision-making and service improvement. But it is often in practice where the enthusiasm wanes.

This is a work in progress. It will help organisations to identify opportunities to improve – or at least ask questions. But it also provides a statement of intent and puts the NHS on a course for finally turning its copious amounts of data into real information and intelligence.

You can register for access to the Model Hospital here

Preparation is paramount for Plymouth

Data verification and engagement with staff

is key to making the most of the data contained in the Model Hospital, according to Laura Langsford (right), Model Hospital programme manager at Plymouth Hospitals NHS Trust.

Building on its role as a Carter pilot site, the trust has been working with the Model Hospital data since the prototype version went live last year. She encourages providers to prepare the ground properly. ‘Before trusts rush ahead with what the data is telling them, data verification is really important,’ she says.

Making sure the data is robust and that the methodology to derive the metric is understood will pay off. ‘If you don’t do this, it can be difficult to talk to stakeholders,’ Ms Langsford says – and it is the engagement with staff that will lead to actual improvements.

She says it is important to realise the data is not absolute. Whether a trust is in a red or green quartile doesn’t automatically mean good or bad, but the trust should understand initially why it is showing that position, and most importantly assess the ability to improve on it.

One early avenue being explored is the trust’s medical staff productivity, with the trust showing a more challenged productivity position compared to its peer group, in relation to medical staff costs. While doctors are becoming more comfortable with the data, Ms Langsford says they must get familiar with their staff cost per WAU metric at a speciality level, and start to get a feel for what it is telling them.

The trust has been engaging with consultants and non-consultants in two formal committees – and it’s paying off. ‘We are starting the financial year in a good place in terms of engagement in improving the metric,’ she says.

One reason for the lower productivity is likely to be about £15m of elective activity undertaken in the local independent sector, squeezed out because hospital capacity has been occupied with increased emergency admissions. But Ms Langsford says elective cancellations, skill mix and outpatient clinic efficiency are also being examined. ‘It is not one single thing, but there is a clearer focus on what a cost improvement programme might deliver and what might contribute to better performance,’ she says.

Finance director Neil Kemsley says Model Hospital data has also ‘reinforced Department of Health data’ in highlighting the opportunity to increase cost recovery from overseas visitors. ‘That metric and the audit work shows we might see a 10:1 return on investment in admin support in this area,’ he says. The trust is also pursuing opportunities to improve its portering productivity metric.

Ms Langsford is clear that data quality is paramount to getting value into the system. But the new data warehouse has ‘brought visibility and allowed us to talk a new language’. It is no panacea, but it provides another tool as trusts look to address the financial challenges facing the NHS.

Related content

We are excited to bring you a fun packed Eastern Branch Conference in 2025 over three days.

This event is for those that will benefit from an overview of costing in the NHS or those new to costing and will cover why we cost and the processes.