Agency staff: keeping out of the red

The NHS in England has undeniably made huge strides forward in reducing its spending on expensive agency staff over recent years. When work began in 2015/16, costs were at an unhealthy 7.2% of overall pay costs and peaked shortly after at 8.2%. Since April 2017, agency costs have been below 5%.

But with the recent forecasts suggesting providers were on course to overspend their centrally set agency ceiling by up to £300m in 2018/19, has the service reached the end of the road in terms of temporary staff cost reductions?

NHS Improvement’s quarter three report showed that actual spending on agency staff was £1.8bn over the first nine months of the year – £139m ahead of the ceiling set by the oversight body. Providers collectively forecast an outturn expenditure of £2.37bn against the full year ceiling of £2.2bn.

In fact, the Q3 report warned that the overspend would be between £200m and £300m by year end. At that level, spending would match the 2017/18 outturn and the overspend would be close to the amount by which the ceiling was lowered.

More than 130 trusts were spending above their ceiling at Q3, according to ratings in the single oversight framework, with 32 trusts overspending by 50% or more.

So, was NHS Improvement too optimistic in lowering the 2018/19 ceiling? Dominic Raymont, deputy director of agency intelligence at NHS England and NHS Improvement, says not.

‘2019/20 will be the fourth year of ceilings. In years one and two, the ceilings were identical and it took until year two to hit the frozen ceiling. Having lowered the ceiling for year three, we’ve frozen it again in year four and we will work with trusts to achieve the ceiling this year.’

Mr Raymont also stresses that the overspend in 2018/19 is down to volume, not rates. Trusts have booked 6%-7% more agency shifts despite plans to reduce them compared with 2017/18. But average prices per shift have fallen by 6%.

The Q3 report provides ample evidence of the pressures driving this volume – A&E attendances up 4.3%, non-elective admissions up 5.4%, elective admissions up 0.7% and first outpatient attendances up 2.1%.

Agenda for Change has contributed to the increase in spending too as agency rates have seen a parallel increase in price caps, although agency commission and framework fees were frozen.

In the face of such pressures, Mr Raymont, says trusts continue to do well in bearing down on agency costs.

Compared with that 8% high a few years ago, agency costs for the first three quarters stood at 4.4% of total pay costs and were forecast to end the year at 4.3% of total pay costs.

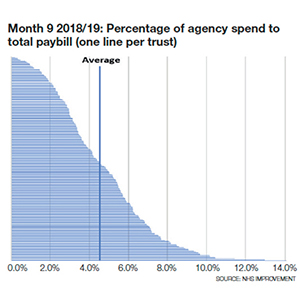

And Mr Raymont is confident that variation between trusts means that agency spending can be reduced further. Compared with that average of 4.4%, agency costs as a proportion of total pay range from practically zero to 14% – with about 10% of trusts being around double the national average or more.

NHS Improvement says there are still some national issues that need to be tackled – including spend on the lower profile use of administrative and non-clinical temporary staff. But beyond that it is about helping some trusts to fix entrenched local factors.

In some ways, he says the big global changes have been put in place – framework rules and rate and price caps. But now there is ‘different work to be done’. This could mean helping trusts with geographical challenges – difficulty to recruit to some positions in some areas not only increases demand for temporary staff, it also suggests it may be difficult to find temporary staff for those positions at a sustainable price.

Another issue for some trusts is dealing with long-term temporary staff. There are still lots of trusts with long-serving agency staff, says Mr Raymont – in the most extreme cases these have been in place for years. ‘A lot of trusts have used our list of the top 10 highest rates paid each week to negotiate different rates or even move them onto bank or to substantive roles,’ he says.

There is now a rich data set in most trusts to support such work and Mr Raymont wants all temporary workforce teams to use this data more proactively. Consultancy Liaison’s Taking the temperature reports track the NHS’s use of locum doctors. The latest puts the projected annual cost of the top 10 highest earning locums in Q3 – working time equal to 16 whole-time equivalents – at £3.7m. Used differently, this could pay the salaries of 42 full-time substantive consultants. Reflecting NHS Improvement’s point, all of these locums had worked consecutively for six months or more and eight had been in post for more than a year.

Some areas still need help establishing or expanding their staff banks too and could learn from good practice across the NHS. At Q3, bank spending was forecast to hit £3.3bn for the full year, £486m (17.5%) over plan and £291m (10%) ahead of last year’s outturn spend. The rise in bank spending in recent years is seen as a success story – its growth avoids the more expensive use of agency staff.

The best way to avoid temporary staff costs overall would be to fill the 100,000-plus vacancies in the service. But while longer term solutions are put in place to improve the availability of appropriately qualified staff to fill substantive positions, banks will continue to play a major role.

The focus for the past two years has been primarily on medical staff banks – fewer trusts had medical staff banks compared with nursing banks. However, by January 2018, 94% of trusts had a medical bank in place or under development and the attention has turned to increasing the effectiveness of these banks.

There has already been some noticeable improvement. On average in 2018/19, 38% of medical temporary staffing shifts went through bank rather than agency – an increase from around one in four shifts in 2017 to more than one in three in the latest year. NHS England and NHS Improvement hope to make more progress on this in 2019/20, informed by a series of pilots – a report on which is due shortly.

Key lessons

Some key messages have already emerged from organisations running successful medical banks. For example, they should be set up on the principle that medical banks are primarily a quality initiative, not a cost-reduction one – with employed staff likely to be delivering a more consistent, better quality service than agency staff. It can be useful to give bank staff first pick of available shifts ahead of agency staff and to accommodate deployment preferences.

Weekly pay and pay commensurate with the agency offer once benefits-in-kind are taken into account can also be important. And enabling doctors to book shifts via smartphones is another key factor.

There are also opportunities to develop staff banks for non-clinical and administrative staff. Medical secretaries and ward clerks have long been provided through banks, but NHS Improvement thinks this could be widened – perhaps particularly for estates staff, where shift work is more likely to be a feature of services such as cleaning and portering.

Reducing agency costs for these non-clinical roles has become the latest focus for NHS Improvement.

Agency workers in non-clinical and unregistered clinical roles – including healthcare assistants, administration, estates and some allied health professionals – currently consume around one-quarter of the total agency spend by trusts.

New proposals, which were consulted on in February and March, look to bring these costs down, by introducing specific restrictions over and above the existing rules set for all agency staff. These are seen by NHS Improvement as the last piece in the jigsaw of national measures to reduce agency spending. If the proposals go ahead, trusts would be required to use only on-framework agencies for shifts involving these staff. Most already do this – but about 37 trusts have been going off-framework in these areas and are responsible collectively for about £7m or 5% of total off-framework spend. (A typical off-framework nursing shift costs nearly 14% more than an average on-framework one.)

‘For nursing, trusts can go off-framework using break-glass procedures if it is a safety issue,’ says Cathy Cawston, head of temporary staffing policy at NHS England and NHS Improvement. ‘But you can’t make that argument as much for admin roles. We’ve seen finance staff bought off-framework. Is that what the break-glass proposals are for? We don’t think so.’

It is more of a change of emphasis than a new rule, she says. ‘The rule has always existed, but we will be monitoring and enforcing it much more closely than we’ve done in the past.’

A second proposal would restrict the use of admin and estates agency staff – currently £223m or 9% of total agency spend. Specific admin agency ceilings are being introduced in 2019/20, alongside proposals requiring trusts to use bank or substantive/fixed-term contracts to fill admin shifts, with exceptions for special projects and clinical coding, for instance.

The message is clear. Reducing agency staff spending is getting harder now that price caps are embedded and more widely adhered to. And volume and activity increases have made the challenge even harder, with safe services being the overriding priority.

Even so, more can be done both in maintaining and improving on existing performance and governance arrangements and in addressing the wide variation that still exists across the country.Controlling costs in the face of rising demand

Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust, like many acute providers, has had a difficult year in 2018/19, with significant financial pressure linked to higher than anticipated demand. A March board paper forecast the trust would deliver a deficit of £40m, £48m the wrong side of its £8m post-provider sustainability surplus control total.

The deficit has been driven by overspends on pay and non-pay, which have resulted in the trust missing its control total and so not receiving PSF income. But regardless of this difficult financial climate and, in particular, significant demand on its emergency department, the trust has continued to keep a check on its agency costs.

After 11 months of the year, the trust’s spending on agency was £1.6m under its agency spending cap. An agency to total pay ratio of 2.6% is lower than the previous year (3%) and well below the national average of more than 4%. At the same time, the trust recently received an ‘outstanding’ rating for caring as part of its overall ‘good’ rating from the Care Quality Commission.

Duncan Orme, the trust’s operational finance director, singles out two initiatives that have helped. ‘We’ve tiered our suppliers of agency staff to try to manage them to be within the rates cap,’ he says. ‘We’ve adopted a win-win approach – if they come in line we give them line of sight of the shifts that need filling. Second is the effective elimination of agencies for healthcare assistants. We promote the use of our internal bank and have taken a proactive approach to developing clinical support workers and recruiting locally.’

The vast majority of general nursing shifts are now within the capped rates. ‘We used to report hundreds of [non-compliant] shifts, but we are now down to 20 per week or so,’ says Lissa Anderson, finance manager providing support to the chief nurse Mandie Sunderland’s team. The few occasions when the trust does have to ‘break glass’ to exceed the rates tend to be for specialist paediatric or critical care nurses. ‘We don’t break glass for general registered nursing use any more,’ she says.

With an outsourced bank service, provided by NHS Professionals, bank staff can book and manage shifts via their smartphones and the trust has introduced a weekly payroll option for its most pressured areas – including junior doctors and emergency department nurses. Can the trust continue to control its agency staff costs in the current climate? ‘Our main focus going forward is how we can afford safer staffing models of care within a tariff set on lower staffing levels,’ says Mr Orme.

There needs to be complete transparency on what is needed to deliver safer staffing levels and then the trust must focus on its average length of stay and optimising flow.Related content

We are excited to bring you a fun packed Eastern Branch Conference in 2025 over three days.

This event is for those that will benefit from an overview of costing in the NHS or those new to costing and will cover why we cost and the processes.