Hospital drugs: on the way down

In 2017/18, drugs spending in hospitals surpassed that in primary care. It was a significant moment. Although the medicines bill in primary care is still rising, efforts to keep spending down – such as no longer prescribing ineffective drugs and national negotiations to keep down spending on branded and generic drugs – appear to be working. But spending in hospitals more than doubled between 2010/11 and 2017/18 and this is now being targeted across the country.

According to NHS England, the overall drugs bill is increasing by 8% a year and much of this rise is being driven by hospital spending. At the beginning of this decade, hospital drug spending was less than half than the value of prescriptions dispensed in primary care – hospitals around £4bn; primary care £8.6bn. Growth in primary care spending slowed, reaching £8.9bn by 2017/18, but over the same period hospital spending increased to £9.2bn.

The reasons for the rapid growth in hospital drug spending are complex. Last year,

the King’s Fund published a report, The rising cost of medicines to the NHS, which warned about the increasing drugs bill. Leo Ewbank, a King’s Fund researcher and one of the report’s authors, says it is difficult to figure out what is driving the rapid increase in hospital costs at national level.

‘I can’t be sure, and I don’t know if the national bodies know what’s going on,’ he says. ‘We found it hard to get a grip of the numbers in a way that felt solid.’

Local providers will have a better grip on the reasons for their costs increases. But generally, it appears that activity increases, rises in the cost of medicines and greater use of specialist drugs are behind it, he says.

A national medicines value programme set up by NHS England aims to ensure that patients can access treatment that is clinically effective, up to date and as low-cost as possible. To reduce waste and increase safety, the programme also wants to give patients support to use their medicines as intended, with appropriate medicines reviews to ensure that outcomes match patients’ expectations.

As well as national policy framework governing access to and pricing of medicines and negotiating commercial agreements with manufacturers, the national value programme plans to optimise the use of medicines. This could include encouraging the uptake of cheaper generic and biosimilar drugs, where appropriate.

Meanwhile, at a more local level, commissioners, providers and systems are also working to bear down on costs while maintaining or increasing safety and quality. These efforts are often carried out under the badge of medicines management, medicines value or medicines optimisation.

North Devon Healthcare NHS Trust, for example, has improved its medicines management pathway for patients receiving acute, unplanned episodes of care. As a first step, paramedics prompt patients being taken to Northern Devon District Hospital to bring their medicines with them. The trust’s mantra is ‘getting medicines right’ – for example, by ensuring it is easier to refer patients to a pharmacist following admission. This can lead to better discharge planning.

The proportion of patients bringing their medicines to hospital rose from 7% in July 2017 to 67% in February 2018 – ward staff can talk to patients about whether the medication is causing any problems. Nursing time is saved as more patients administer their own medication, unintended omissions have reduced and there was less waste.

One system tells Healthcare Finance that it has set up several projects to reduce spending, including a gain share agreement to combat recent growth in high-cost drug costs. This is introducing oversight and cost reduction, influencing the provision of drugs for home care and the choice of product. The gain share is operating for a fixed period, incentivising providers to switch patients onto lower cost biosimilars. ‘There is an incentive to ensure the process is done rapidly and to ensure there are enough resources to enable the transition to take place,’ it says.

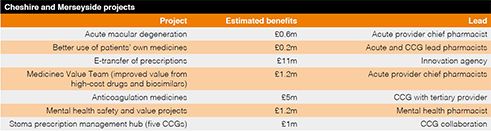

Elsewhere, a system-wide medicines optimisation programme has been set up under Cheshire and Merseyside Health and Care Partnership. The collaborative programme is led by independent chair, Helen Poulter-Clark, chief pharmacist from The Clatterbridge Cancer Centre, and Chris Harrop at NHS-hosted assurance and advisory service MIAA Solutions, with non-recurrent funding from the sustainability and transformation partnership.

The programme aims to increase and sustain a minimum 90% uptake of biosimilar medicines. It is also leading on other, at scale, projects, such as e-transfer of prescriptions; promoting better use of patients’ own medicines and encouraging optimal prescribing of alternatives to traditional anticoagulants like heparin and warfarin. These alternatives are known as direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs).

Previously, two groups were looking at medicines optimisation locally – one developed by NHS England with a commissioner perspective on high-cost drugs and biosimilars; the other provider based. The latter was examining a limited list of drugs that it felt it could influence, such as medicines used to treat some cancers and age-related macular degeneration. ‘It struck me that it didn’t make sense to look at it from just one perspective and, over the course of about six months, we started to pull together a common agenda,’ says MIAA’s Mr Harrop. ‘We have achieved a great thing in having one group looking at medicines optimisation across the whole region.’

Mr Harrop doesn’t pretend Cheshire and Merseyside has got everything right, or that its approach is unique. ‘It’s a work in progress,’ he says, adding that the biggest difference is the system-wide nature of the medicines optimisation programme.

Initial meetings between the groups were followed by a series of workshops and now the establishment of four core project groups.

Each core project (see table) is led by a chief pharmaceutical officer.

Savings from the medicines value project could be in the millions, he says. ‘Providers in Cheshire and Merseyside are already doing quite well on a range of medicines optimisation indicators, but to get to 90% uptake of biosimilar medicines for all providers, for example, could lead to millions of pounds in potential costs avoided.’ Sharing learning and intelligence across the system is invaluable, he says.

Ms Poulter-Clark adds: The programme offers the opportunity to collaborate beyond traditional working networks and has enabled local expertise to achieve cross-organisation benefit. We are beginning to see real change and are keen to make sure lessons are shared in the NHS with national programmes.’

Susanne Lynch (pictured), head of medicines management at South Sefton Clinical Commissioning Group and Southport and Formby Clinical Commissioning Group, says the two Sefton CCGs have a well-established shared medicines management team made up of clinical pharmacists, technicians and an analyst.

‘The team is always looking for savings, efficiencies and innovation to optimise prescribing in primary care, but the Cheshire and Merseyside work is an opportunity to work with colleagues across the sectors and to start thinking as a system,’ she says. ‘From a financial perspective for some projects we could look at, both commissioner and provider will gain. In some, it will be one party, but that’s the challenge of system working. It’s not about them and us.’

She welcomes the system-wide working. The days are gone when it was enough to switch a drug locally for a cheaper option to achieve financial balance and best patient outcomes. The future requires managed medicines optimisation across systems and sectors. ‘It’s a real opportunity for pharmacists to start to make a difference and to share best practice,’ she adds.

Locally, the South Sefton and Southport and Formby CCGs’ medicines management team is working with primary care networks (PCNs) and local trusts to review, optimise and reconcile patients’ medicines after hospital discharge. ‘We are working with our community pharmacy colleagues and care homes to support patients post-discharge with regard to medication changes and making adjustments to meet personal needs,’ says Ms Lynch. ‘This will ensure quality and safety and a smooth transition from hospital to community.

With system working, pharmacists can really support patients, she says. National investment in clinical pharmacists along with investment from individual CCGs in medicines management teams such as in the two Sefton CCGs enables working at scale rather than in silo.

Joined up leadership is also key. ‘What we do as a team is not all about saving money, as when we visit or speak with patients, we can make interventions or signpost patients, which delivers quality outcomes for everyone. It is important to listen to what matters to a patient about their medicines when reviewing them,’ she adds.

‘If pharmacy teams are doing good quality reviews across the sectors in a joined-up way, there could be significant savings to the system, along with benefits for the individual patients.’

Use of DOACs

The use of DOACs is increasing locally and nationally. Cheshire and Merseyside is focusing on how DOAC prescribing can be better optimised. Clinicians want to be sure patients are getting the best medical outcomes from this new group of drugs in a cost-efficient way. The potential savings are significant across the system.

Ms Lynch is leading the project. ‘The programme is about reviewing patients being prescribed DOACs to improve quality and where appropriate deliver cost savings. Scotland has undertaken work already in this area, so I’ve been in touch with them – it’s great to learn from others what’s working for them,’ she says.

Mr Harrop says the cost benefit of the DOAC project could be around £5m, based on clinical and cost effectiveness studies undertaken elsewhere in the UK. In mental healthcare, there is a potential further opportunity to improve patient safety by reviewing patients in certain high-risk groups more frequently, he says. Based on evidence from within Cheshire and Merseyside, this could avoid costs of £1m to £1.5m by reducing exacerbations and improving compliance, for example by being sure the person is taking the medicine as intended. However, he adds that the opportunities will need to be validated with the three local mental health providers.

‘There is a clear narrative of making sure all these projects are sustainable through support from clinicians, patient safety and cost avoidance,’ Mr Harrop says.

While there is an opportunity to bring clinicians together from across the system, there is an acknowledgement that, at place level, the situation can differ. A place with one acute provider, a mental health trust, local authority and clinical commissioning group will be less complex than a city like Liverpool, which has general and specialist providers. ‘You have to be careful to make sure you disaggregate the work and ensure ownership of projects within place,’ he adds.

The programme is speaking to other areas interested in replicating what it has done. ‘It could be used elsewhere, but it would be difficult to replicate the relationships and understanding of the people in the system. The approach would be the same – bringing people together on a common agenda with common reporting.’

The NHS must get to grips with the growth in hospital drugs spending if it is to ensure that it is getting value for money from every pound spent. Local and system-wide schemes, complemented by national programmes, appear to be having an effect. But, as is often the case with collaborative projects, those most likely to succeed are the ones where relationships are strong and organisational requirements are secondary to those of patients.

Resources required

Realising the benefits of medicines optimisation and value work often depends on having the resources at ward level to ensure any changes are introduced safely and effectively, says Pippa Roberts, director of pharmacy and medicines optimisation at Wirral University Teaching Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, and system lead for the Wirral medicines optimisation programme.

She says Cheshire and Merseyside medicines optimisation work focuses on hospitals’ approach to value, safety and cost-effectiveness. Collaboration is helpful, ensuring the spread of best practice and that effort is not duplicated.

The speed of adopting a change in medicine use varies between hospitals, often due to a lack of implementation resources. Introducing drugs is not just a question of the product being available, but having pharmacists and clinicians ready to shepherd them safely and effectively into the front line, she adds.

Initially, it was estimated that the medicines value team’s focus on high-cost drugs and biosimilars would save £1.2m a year across the health and care partnership. However, the actual savings could be higher.

Bringing in biosimilar drugs, particularly bringing all trusts up to the same level of use, has been a priority for Cheshire and Merseyside.

‘Our work has identified that the introduction of biosimilars requires resource, and while some trusts were doing the work by redirecting available internal resource or as a result of local funding, an impasse has been reached for some, due to a lack of pharmacy resource to safely drive the switch,’ says Ms Roberts. ‘Resource has been inextricably linked to the speed of adoption with these medicines and has led to lost opportunities where trusts have not been on the front foot with the resources to plan in advance and implement at the earliest opportunity.

‘In the Wirral, we have received resource as part of an invest to save scheme agreed with Wirral Clinical Commissioning Group to introduce biosimilar versions of “mab” drugs.’

These drugs can be used in a range of health conditions, including Crohn’s, ulcerative colitis and psoriasis, and includes adalimumab (used to treat rheumatoid arthritis), the service’s most costly drug. Last year, NHS England reached an agreement with manufacturers of biosimilar versions of the drug, which could save the NHS £100m a year.

Overall, savings from the introduction of biosimilars in place of mab drugs have reached almost £3m in the Wirral since the review programme started. Ms Roberts says this was only possible because her team was funded and prepared. ‘We had the resources in place when the biosimilars came – we switched 90% of the patients on adalimumab in the first month and we had been communicating with them on the change six or seven months prior to that.’

Related content

We are excited to bring you a fun packed Eastern Branch Conference in 2025 over three days.

This event is for those that will benefit from an overview of costing in the NHS or those new to costing and will cover why we cost and the processes.